A Mountain Legacy Remembered A Cultural Bloom in the Heart of the Forest Just east of Portland, along the winding curves of Highway 26, sits Rhododendron, Oregon—a place not quite a town, but more than a roadside stop. Nestled in the folds of the Mount Hood National Forest, it’s a patchwork of tall trees, weathered … Continue reading Curtains in the Forest: Rhododendron Summer Theater

Tag: Welches Oregon

The Legendary Mrs. Pierce: She Killed a Bear With Her Hoe

I’ve spent a lot of time talking with old-timers and the family members of folks who’ve lived up here in the Mountain Community for years. In one or two conversations, I’d heard tell of a woman who gained local notoriety for killing a bear that invaded her space with a garden hoe.

Henry and Fred Steiner Deaths in the Mount Hood Forest

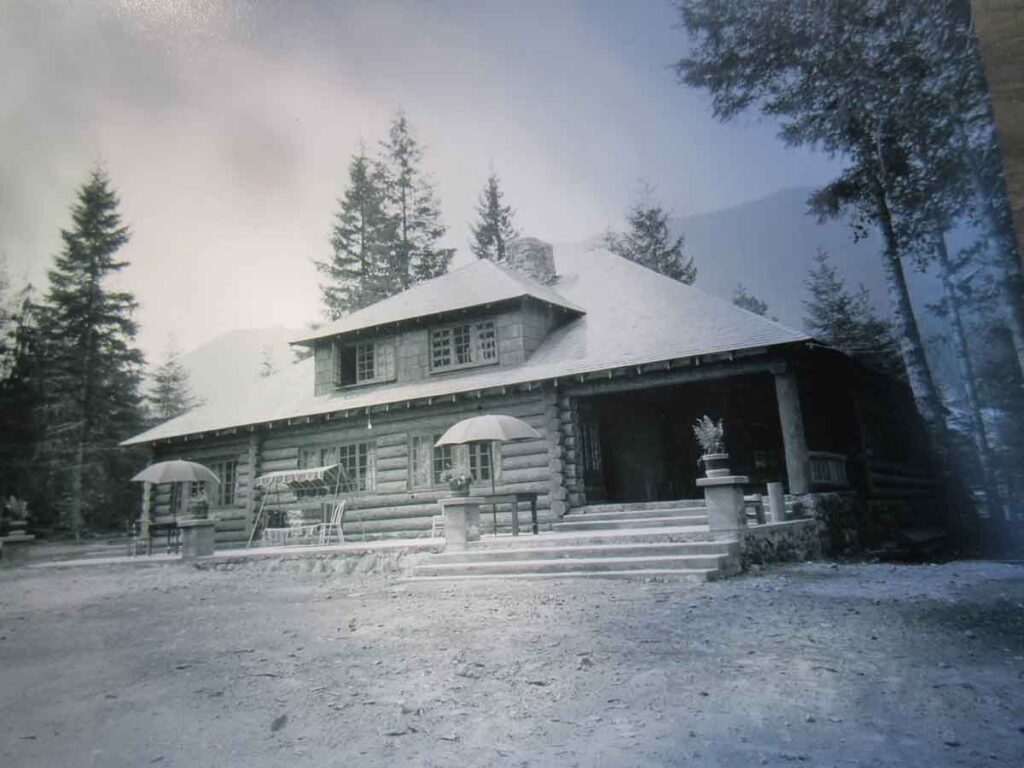

Henry Steiner was known throughout the Mount Hood region as a master builder of log homes. He and his wife, Mollie, raised their family in Brightwood, where Henry built dozens of rustic cabins that still stand today.

Mount Hood Auto Stages: From Rugged Roads to Modern Highways

In the early 20th century, long before travelers zipped up Highway 26 to the ski lifts and resorts of Mount Hood, the trip to the mountain was rugged and uncertain. The road, built on the bones of the old Barlow Trail, was steep, narrow, and either muddy or dusty depending on the season.

Burnt Lake Fire 1904: How the Lake Got Its Name

The Burnt Lake Fire of 1904 swept through this area, leaving damage so severe that the lake was named for it. Though the forest has mostly grown back, signs of that fire still linger, more than 120 years later.