The Rise and Fall of Primitive Travel on the Old Barlow Road

The Early Days of the Mount Hood Auto Stages

In the early 20th century, long before travelers zipped up Highway 26 to the ski lifts and resorts of Mount Hood, the trip to the mountain was rugged and uncertain. The road, built on the bones of the old Barlow Trail, was steep, narrow, and either muddy or dusty depending on the season. For those without their own means of transportation—and even for those who did—reliable travel meant trusting the early Mount Hood auto stages and their legendary drivers who knew every twist, rut, and washout of the mountain road.

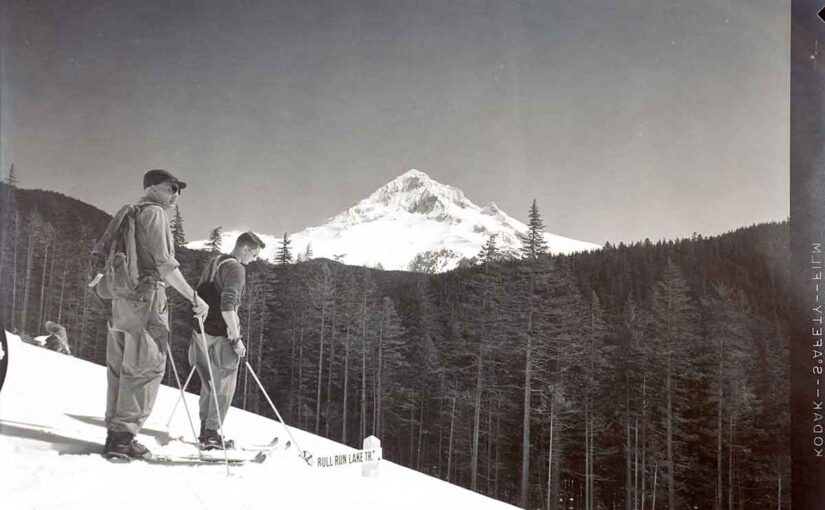

The Route to the Mountain

Before the 1880s, travelers followed the original Barlow Trail, carved out by immigrant wagon trains in the 1840s to the 1860’s. This immigrant trail came from Central Oregon and passed over Mount Hood’s southern shoulder. The route took travelers through the area that we know today on the south side of Mount Hood. Coming down from the mountain the route followed the north side of the Zigzag River and then crossed the Sandy River to the north side and through what we now know as Marmot. This remained the primary route until settlement increased east of Sandy.

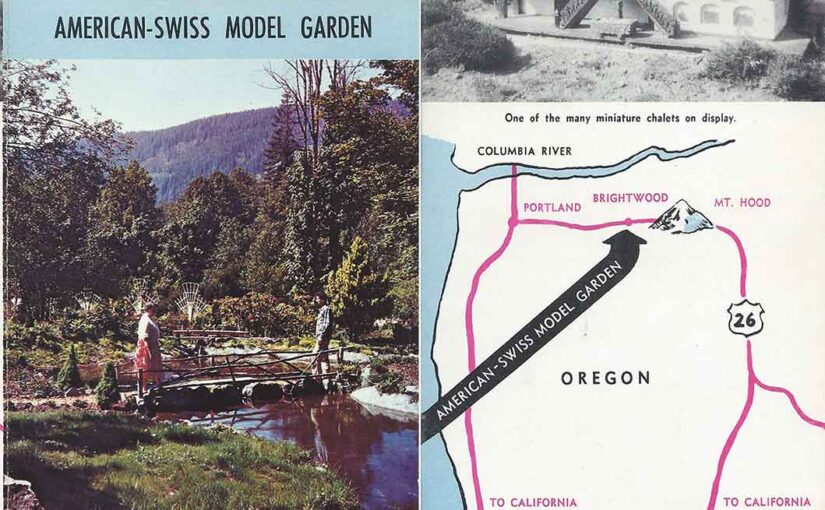

In the 1880s, a new south side road connected Sandy to Government Camp by following the south bank of the Sandy River. This alternative offered gentler grades, primitive but useful bridges creating more reliable access. Consequently, it soon became the main road to and from the mountain. Meanwhile, the Marmot Road continued as a scenic alternate, especially for travelers heading to Aschoff’s Mountain Home.

The primary route—used by both stagecoaches and auto stages—passed through Sandy, Cherryville, Brightwood, Welches, Zigzag, Rhododendron, and Government Camp. Notable stops included the Cherryville Hotel, Welch’s Hotel, Tawney’s and the Rhododendron Inn, and others.

The Stage Lines and Their Drivers

Initially, travelers relied on horse-drawn stages operated by local residents. Joe Meinig and Walter Ziegler were among the best-known drivers in those early days. However, as the road improved and mountain tourism grew, motorized stages entered the picture.

By the 1910s, auto stages had largely replaced horse-drawn wagons. Bob Elliott, a Sandy garage owner, led the way with one of the first regular lines to Government Camp. His rugged fleet of Pierce-Arrows, Cadillacs, and White touring cars came equipped with chains, spare tires, and tools for inevitable roadside repairs.

One of the most prominent operations was Reliance Mount Hood Stages. They offered daily trips from Portland’s eastside waterfront and coordinated with nearly every lodging stop along the route. Their Touring Cars became a familiar sight climbing the dusty grades to Rhododendron and beyond.

Among the legendary drivers was Dr. Ivan M. Wooley. His memoir, Off to Mt. Hood – An Auto Biography Of The Old Road, preserves vivid recollections of the people, places, and perils of early auto stage travel. His storytelling has given us one of the richest surviving records of this vanished era.

Hard Roads and Gritty Travel

Despite the switch from horses to horsepower, travel remained difficult. The roads were merely widened wagon paths. On steep hills like Laurel Hill and McIntyre Hill, passengers often had to walk. The latter, near Brightwood, posed such a challenge that hotelier John McIntyre charged motorists a fee to haul their cars up the grade with his horses. Eventually, widening the road, regrading the hills and decreasing the grades helped. Still, early autos struggled.

Drivers had to wear many hats: mechanic, navigator, and even peacemaker. They fixed broken axles, crossed flooded creeks, and comforted uneasy passengers. Some vehicles towed freight. Others had canvas tops for sun and rain. The trip could last all day, but for many, that was part of the fun.

Mountain Tourism and the Resorts That Made It Possible

The auto stages helped turn Mount Hood into a major Oregon destination. Easier access drew tourists eager to escape city heat or enjoy snowy slopes. Resorts like Welch’s Ranch, Arrah Wanna Lodge, Tawney’s Mountain Home, and the Rhododendron Inn thrived. They offered lodging, camping, hearty meals, hunting, fishing, hiking, dances and community bonfires. Most worked directly with stage lines, ensuring guests could be dropped off at their doorsteps. Back then, the journey, the lodging, and the scenery created a complete experience.

The Automobile Takes Over

By the mid-1920s, personal automobiles had changed everything. Tourists no longer needed to reserve stage seats. They could drive, stop where they pleased, and enjoy more freedom. Ironically, the new Mount Hood Loop Highway—built to improve access—also ended the era of the auto stage. Independence had arrived.

The End of the Line for The Mount Hood Auto Stages

In 1923, the Mount Hood Loop Highway was completed, dramatically altering travel to the mountain. With the addition of a road to Hood River on the east side, the full loop was in place.

As roads improved and cars became more dependable, scheduled auto stages became obsolete. Tourists drove themselves, and although the mountain resorts endured, the days of colorful drivers and mechanical struggles quietly faded away.

Love Mount Hood History?

Discover more local stories, rare photos, and forgotten places:

- Historic Photos

- Mount Hood Pioneers

- Welches & Rhododendron

- Barlow Road Stories

- Lost Resorts & Landmarks

Follow the trails. Meet the people. Uncover the past.