A Place of Cultural Significance

It’s not commonly known, but our home on the slopes of Mount Hood is a place of deep cultural importance. For generations, Mount Hood’s Native people traveled here each season, arriving from all directions between spring and autumn to live, hunt, trade, and gather resources.

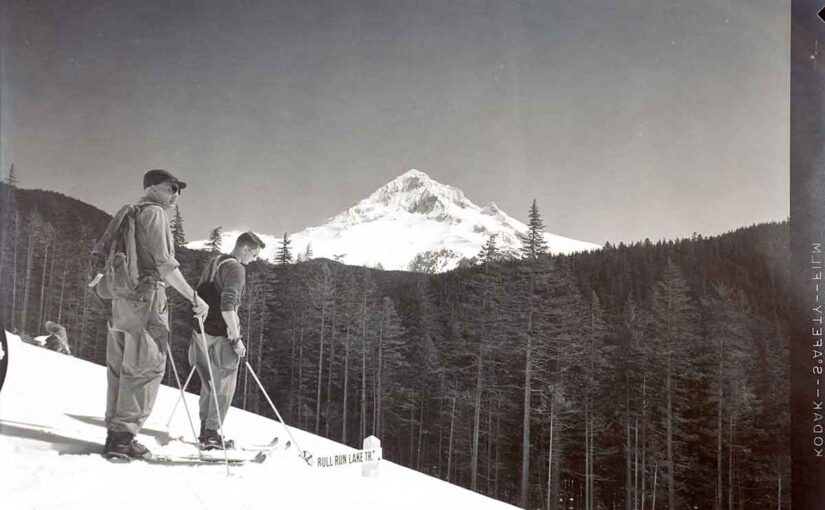

The place that we call Zigzag today was once a convergence point for three important ancient trails:

- One trail came from the Columbia River Gorge, following what is now called Lolo Pass.

- Another came from Central Oregon, crossing the south side of Mount Hood—a path that parts of the Barlow Trail later followed.

- The third arrived from the west, connecting to the Willamette Valley.

Seasonal Gatherings and Traditions

Although the native people travel and would hunt in this area all year long, each Spring tribes from all around Mount Hood gathered in ancestral camps along the rivers between Government Camp and the town of Sandy, especially at the the confluence of the Sandy and Salmon Rivers. They returned to places that their families had been coming to for centuries.

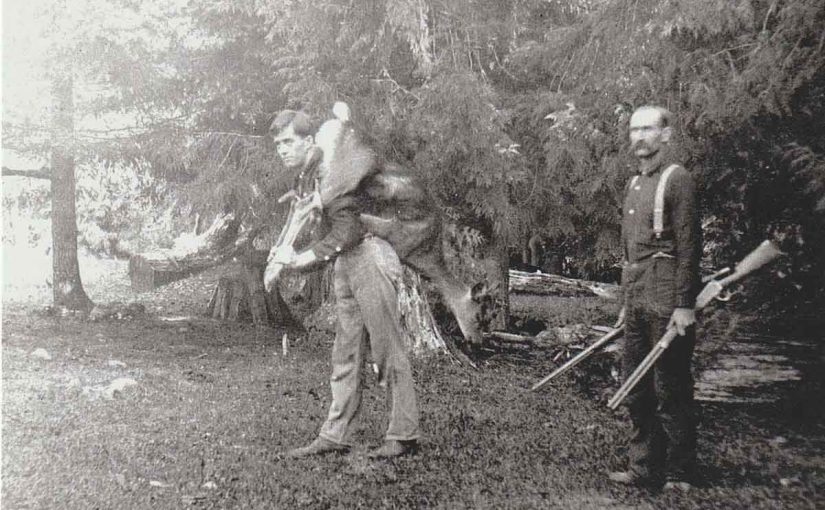

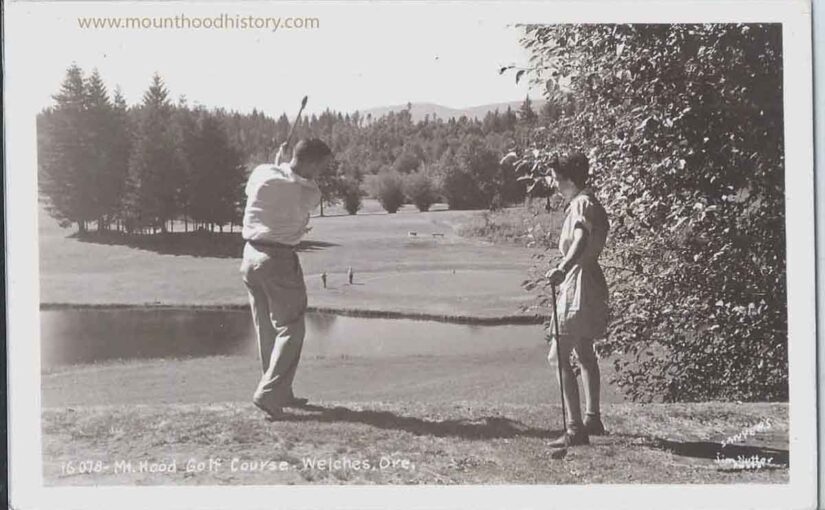

The purpose of these gatherings was to harvest essential resources and trade with other visiting groups. While the men hunted and fished, the women also fished, harvested food, medicinal roots, and herbs from the area’s plentiful wetlands. They also collected huckleberries on the surrounding hillsides and carefully prepared their bounty for transport back to their winter homes. They would also play games and race horses.

A Tradition That Faded with Time

For thousands of years, these seasonal gatherings remained a vital part of life in this region. However, by the late 19th century, they began to disappear. As disease reduced the Native population and forced relocations to reservations increased, the annual traditions slowly faded.

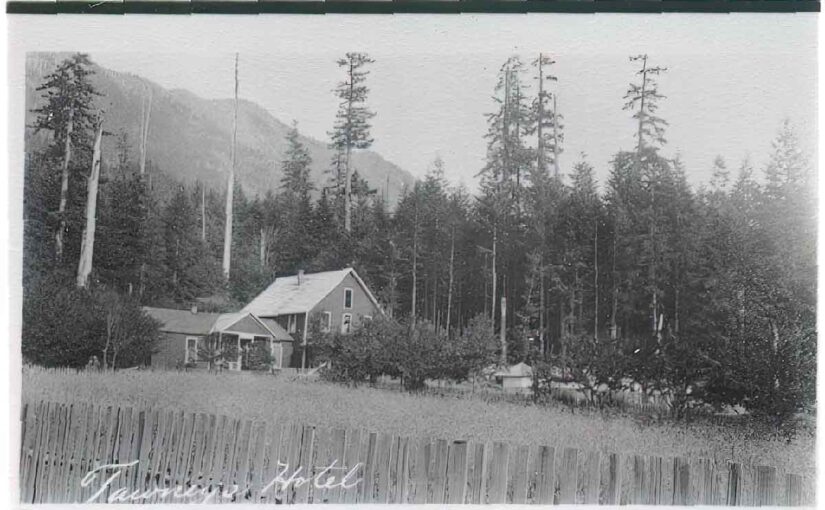

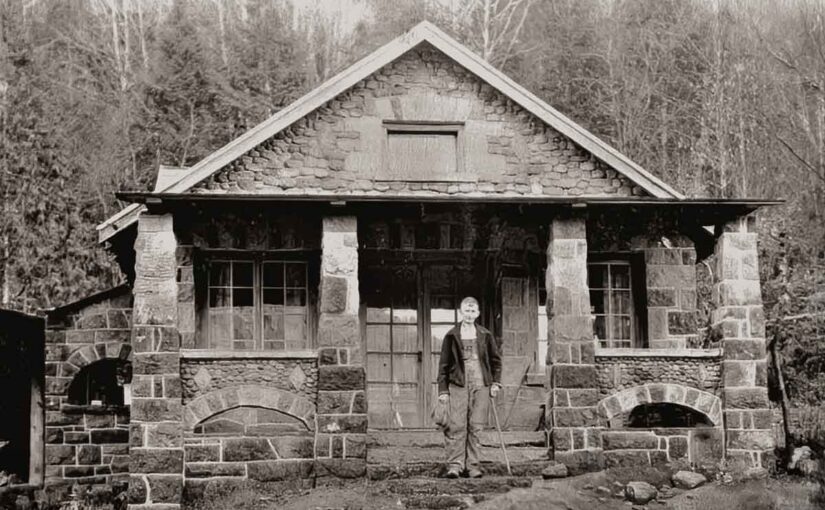

Samuel and Billy Welch coexisted with the Native people for some time. However, as non-Native settlers arrived to recreate and establish permanent homes, the presence of the original inhabitants diminished.

A Continued Presence in the Region

Even after their seasonal camps had vanished, Native people still traveled along the Barlow Trail from Warm Springs to the Willamette Valley. Many brought herds of horses or sheep to sell. They often stopped overnight in Welches, where Billy Welch provided corrals for their animals.

Honoring the Past

In today’s world, it’s hard to imagine the land we call home as it once was—teeming with life, culture, and tradition for thousands of years. It may seem like distant history, yet in reality, it wasn’t that long ago.

The history of Mount Hood is deeply intertwined with the history of its Native people. Their stories, trails, and traditions are still woven into the landscape, reminding us of those who came before us.