When Live Bears Entertained Tourists Pet Bears Were Once a Common Sight at Government Camp In the 1920s and ’30s, tourists came to Mount Hood for snow, scenery, and rustic lodging. But for a short time, they also came to see the Government Camp bears. Lodges in Government Camp kept live bear cubs on-site. These … Continue reading Government Camp Bears: Mount Hood’s Forgotten Mascots

Tag: government camp

Mount Hood Auto Stages: From Rugged Roads to Modern Highways

In the early 20th century, long before travelers zipped up Highway 26 to the ski lifts and resorts of Mount Hood, the trip to the mountain was rugged and uncertain. The road, built on the bones of the old Barlow Trail, was steep, narrow, and either muddy or dusty depending on the season.

Baby Morgan’s Grave: A Tragic Pioneer Story at Summit Meadow

Tucked in the peaceful meadow near Government Camp, Oregon, lies a quiet grave that tells a heartbreaking story. Baby Morgan’s grave is marked by a small bronze plaque mounted on a random boulder named Chimney Rock

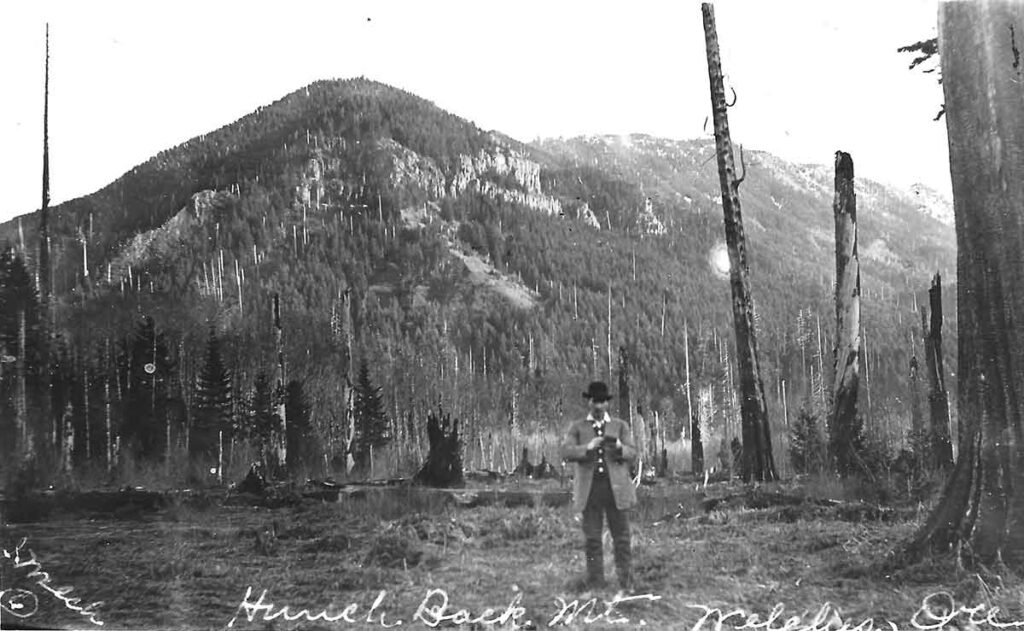

Mount Hood Forest Fires of 1910

The Big Burn, or as it was called, “The Big Blowup” saw huge fires in the whole of the Northwest including Idaho, Montana and Washington. Although it wasn’t considered a part of the Big Blowup, that August a wildfire threatened to burn down the towns between Sandy and Government Camp.

Map Curve, Is it Natural, or Man Made?

Map Turn is the sweeping curve located west of Government Camp — just downslope from the new truck escape ramp — where several persons have perished in auto accidents in recent years.