When Live Bears Entertained Tourists Pet Bears Were Once a Common Sight at Government Camp In the 1920s and ’30s, tourists came to Mount Hood for snow, scenery, and rustic lodging. But for a short time, they also came to see the Government Camp bears. Lodges in Government Camp kept live bear cubs on-site. These … Continue reading Government Camp Bears: Mount Hood’s Forgotten Mascots

Category: Towns

Towns

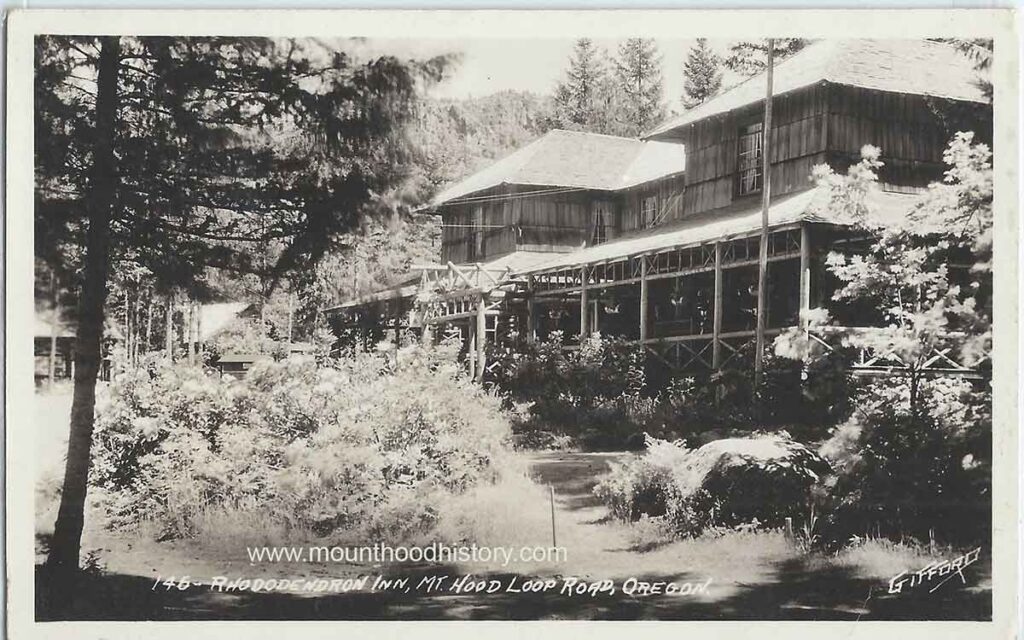

Curtains in the Forest: Rhododendron Summer Theater

A Mountain Legacy Remembered A Cultural Bloom in the Heart of the Forest Just east of Portland, along the winding curves of Highway 26, sits Rhododendron, Oregon—a place not quite a town, but more than a roadside stop. Nestled in the folds of the Mount Hood National Forest, it’s a patchwork of tall trees, weathered … Continue reading Curtains in the Forest: Rhododendron Summer Theater

Bob Gambell Interview – A Brightwood Life Remembered

A Conversation at the Brightwood Tavern, 2009 Bob Gambell Tells It Like It Was, Preserved in His Own Words In 2009, I sat down for an interview with Bob Gambell at the Brightwood Tavern. Bob was a longtime resident of our mountain community, and he had lived a full, eventful life. In this interview with … Continue reading Bob Gambell Interview – A Brightwood Life Remembered

Scandal in Cherryville: The Man Who Guarded a Grave

In the summer of 1911, the Friel case in Cherryville Oregon became one of the most disturbing stories ever told from the Mount Hood foothills. A suspicious death, a hurried marriage, a missing medicine bottle, and an armed grave watch pushed a grieving family to the brink of collapse.

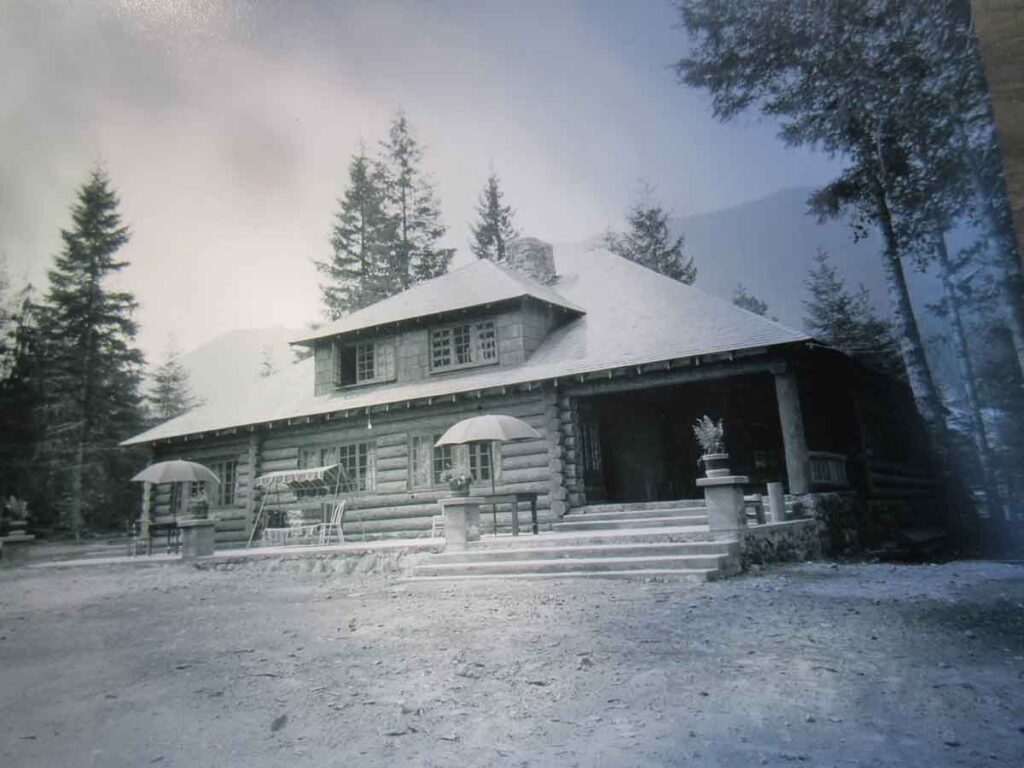

Susette Franzetti Rhododendron Oregon – Pioneer Innkeeper

Before Rhododendron, Oregon, became a known mountain getaway, Susette Franzetti helped build its identity. A Swiss hotelier with European training, she transformed the area with hospitality, real estate, and resilience.