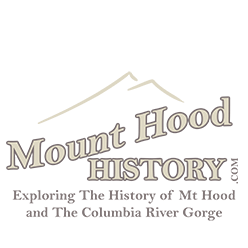

When Live Bears Entertained Tourists Pet Bears Were Once a Common Sight at Government Camp In the 1920s and ’30s, tourists came to Mount Hood for snow, scenery, and rustic lodging. But for a short time, they also came to see the Government Camp bears. Lodges in Government Camp kept live bear cubs on-site. These … Continue reading Government Camp Bears: Mount Hood’s Forgotten Mascots

Category: Mt Hood Loop Highway

Mount Hood Auto Stages: From Rugged Roads to Modern Highways

In the early 20th century, long before travelers zipped up Highway 26 to the ski lifts and resorts of Mount Hood, the trip to the mountain was rugged and uncertain. The road, built on the bones of the old Barlow Trail, was steep, narrow, and either muddy or dusty depending on the season.

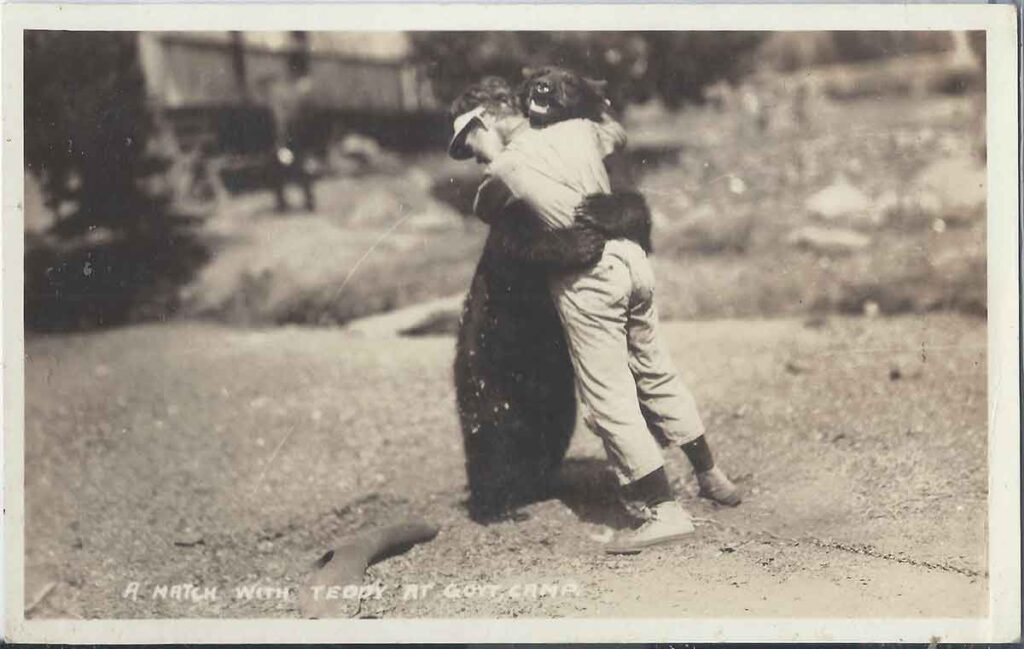

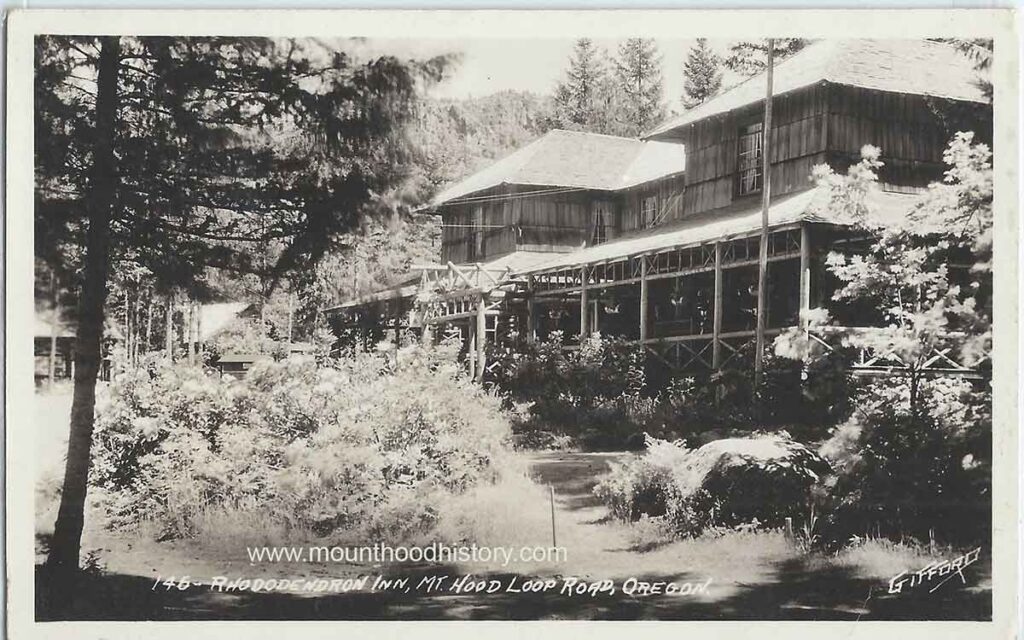

Susette Franzetti Rhododendron Oregon – Pioneer Innkeeper

Before Rhododendron, Oregon, became a known mountain getaway, Susette Franzetti helped build its identity. A Swiss hotelier with European training, she transformed the area with hospitality, real estate, and resilience.

Emil Franzetti Rhododendron Inn – Mount Hood’s Gourmet Chef

Before ski resorts dotted the highway and travelers packed the trailheads, Emil Franzetti of the Rhododendron Inn brought elegance and fine cuisine to Oregon’s Mount Hood region.

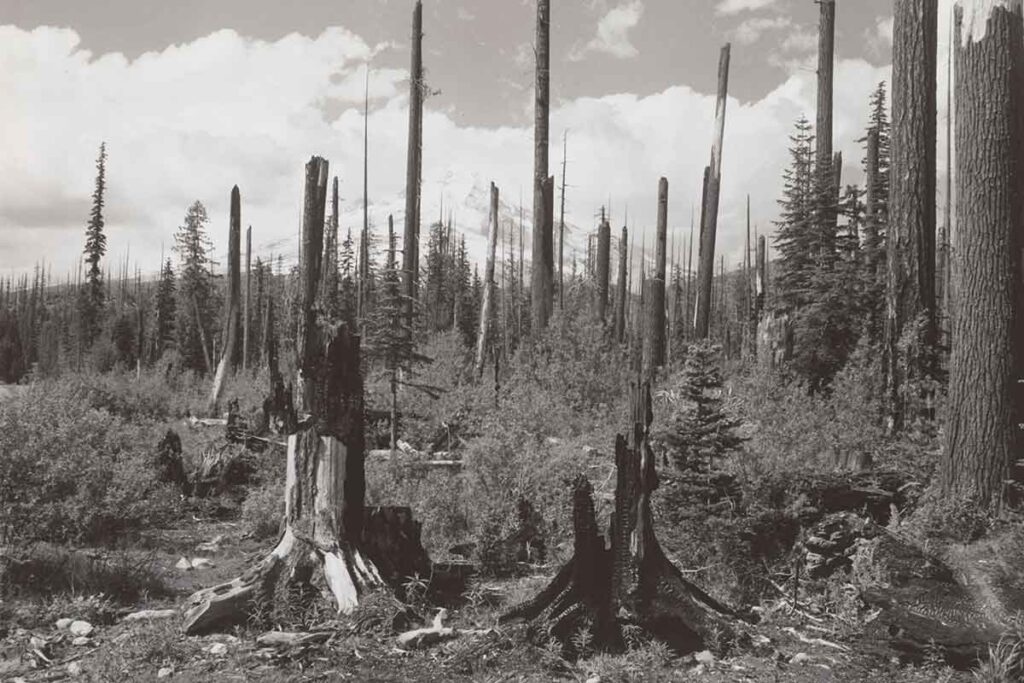

Burnt Lake Fire 1904: How the Lake Got Its Name

The Burnt Lake Fire of 1904 swept through this area, leaving damage so severe that the lake was named for it. Though the forest has mostly grown back, signs of that fire still linger, more than 120 years later.