Snowplow on Mt Hood Loop Highway circa 1950-ish. The winters of 1949-1951 were big snow season’s on Mount Hood.

This scene is most likely on the road to Timberline Lodge.

Snowplow on Mt Hood Loop Highway circa 1950-ish. The winters of 1949-1951 were big snow season’s on Mount Hood.

This scene is most likely on the road to Timberline Lodge.

Here’s a great story from 1958 about driving through Oregon’s Lolo Pass Road back when it first opened. It tells about how, after it was determined that the area was not a part of the Bull Run Lake watershed, the road was built in 1955 opened to the public from Spring until Fall for fantastic views of Mount Hood’s west side.

For decades, travelers along U.S. Highway 26 in Oregon have been greeted by a unique roadside landmark: the towering Ivy Bear at Alder Creek. Covered in thick vines and steeped in local lore, this massive figure has become a beloved symbol of the Mount Hood area. Built as a tribute to a pet bear, it eventually collapsed, but thanks to a dedicated community, it rose again.

The story of the Ivy Bear begins with Gerald Wear, a deaf craftsman, dog trainer, and builder who lived in Alder Creek. Wear was widely known for his ingenuity and deep love for animals. Alongside training German Shepherds, he also cared for a bear that lived in a roadside cage. As travelers passed along the two-lane highway, many stopped to watch the bear, which quickly became an unofficial mascot.

Eventually, the bear passed away. According to local accounts, it died after consuming too many candy bars, soda pop, and bottle caps handed out by curious onlookers. Heartbroken, Wear felt compelled to honor the animal. He decided to create a much larger tribute: a towering ivy-covered bear that would stand beside the road for all to see.

In 1947, Wear began construction on what would become the Ivy Bear at Alder Creek. He built a wooden frame, wrapped it in chicken wire, and carefully planted ivy around the structure. Over the course of more than a year, the vines filled in, eventually covering the entire bear.

At the time, the figure was believed to be the largest ivy-covered structure in the world. Motorists quickly became accustomed to the sight of the massive bear keeping watch near the highway. To make the figure even more lifelike, Wear added a rear door and scaffolding inside that led up to the bear’s head. At night, he would climb inside and light its eyes with candles. Later, he upgraded them with old Volkswagen taillights.

Over time, the Ivy Bear at Alder Creek became even more popular. In fact, it eventually became better known than the businesses located on the property. Mount Hood skiers adopted a tradition of saluting the bear for good luck, and children often lifted their feet as they passed by.

Meanwhile, Wear continued working on creative projects in Alder Creek. In addition to the bear, he built homes and decorative water wheels. Although Wear passed away in 1972, his most famous creation remained standing—a lasting testament to his creativity and love for the area.

After nearly 40 years of standing tall, the Ivy Bear collapsed on June 18, 1984. A gentle breeze that evening was all it took to bring down the aging wooden structure. The bear toppled forward and landed on its tin snout.

Upon closer inspection, the cause became clear: the wooden beams at the base had rotted through. Without a strong foundation, the structure simply gave way. Although exterior damage was minimal, the bear could no longer stand upright.

The loss resonated with the community. Travelers slowed down, searching for the familiar landmark. Even the Portland Chamber of Commerce reached out to the property’s owners, eager to help restore the iconic roadside figure.

Recognizing the Ivy Bear’s cultural value, local residents and organizations launched a campaign to bring it back. In 1987, Ron Rhoades, owner of the Ivy Bear Restaurant, partnered with Michael P. Jones of the Cascade Geographic Society and the Friends of the Ivy Bear to start a fundraiser.

By 1990, their efforts paid off. The community raised enough money to rebuild the Ivy Bear—this time using a steel frame designed to withstand time and weather. Thanks to their perseverance, the Ivy Bear stood once again.

The bear’s revival brought renewed energy to the Mount Hood area. Locals and travelers alike celebrated the return of the iconic figure. Once more, the Ivy Bear stood proudly along Highway 26, welcoming visitors and honoring its unique history.

Today, the Ivy Bear remains a bit overgrown but continues to charm passersby. It stands not only as a tribute to Gerald Wear’s craftsmanship and compassion but also as a symbol of community pride. Next time you drive through Alder Creek, don’t forget to salute the bear—just like generations before you.

“Booming Business – Tiny Brightwood post office will soon be upgraded in status, and position of officer in charge will be changing to postmaster. Kay Hudon, who’s now officer in charge, is applying for the new job.”

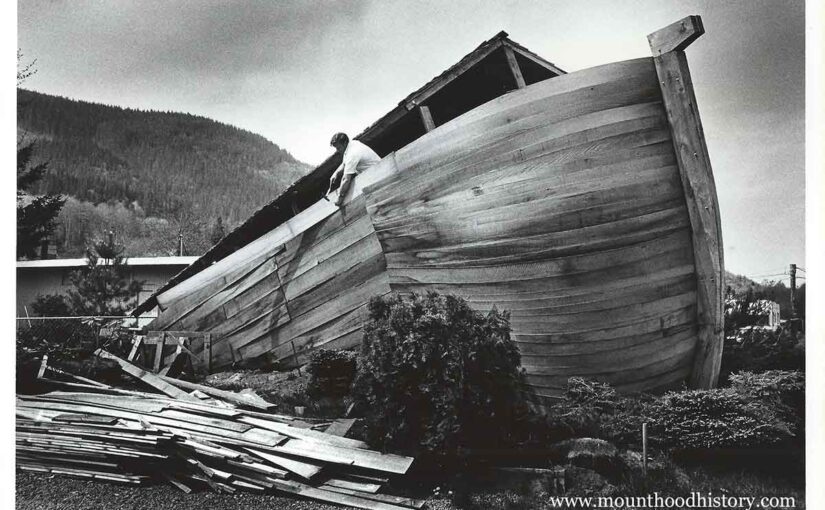

April 17, 1985. The Oregon Ark Motel.

“Richard Lightbody, owner of Oregon Ark Motel, puts final touches on “ark” he is building out of bender boards, even though area has had fewer than 40 days of rain a year. He said ark was not meant to save souls but to attract attention to his motel on U.S. 26, which he has owned since June.”

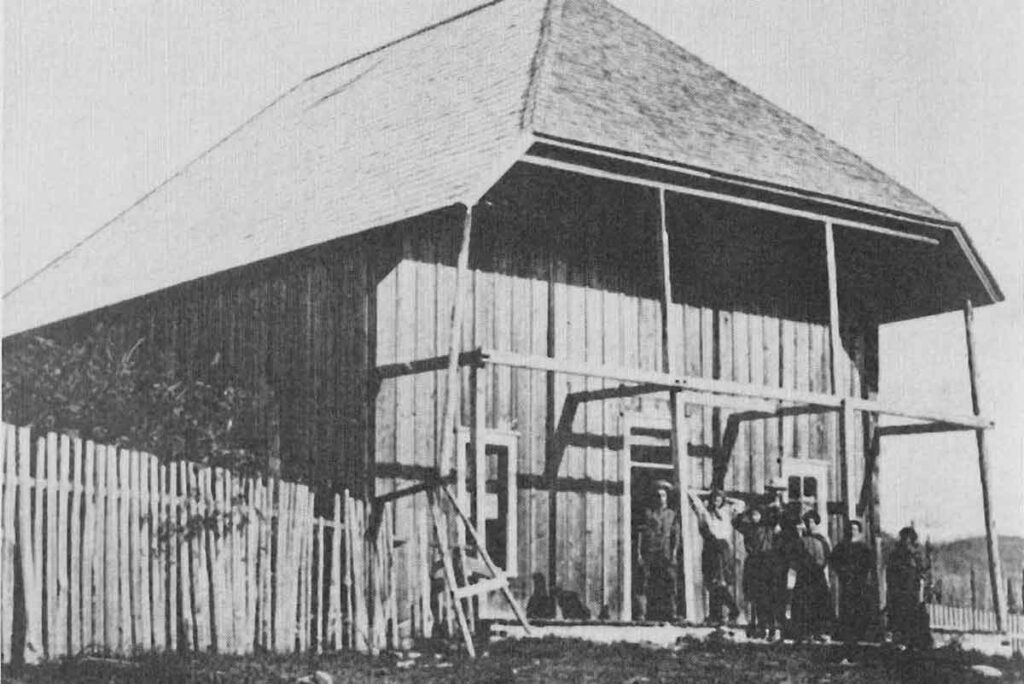

The old Welches School which was located at the intersection of Welches Road and Highway 26, Welches, Oregon.

When people think of Mount Hood, crime usually isn’t the first thing that comes to mind. Especially not murder. Yet, one story from Mount Hood’s past should be told—the mountain’s first recorded murder. This is the story of the first Murder on Mount Hood.

For about 40 years, the Oregon Trail carried settlers west, and became the main route into the Willamette Valley. Samuel Barlow and Joel Palmer blazed the trail over the south shoulder of Mount Hood. Soon after Barlow made the trail a toll road. Tollgates were placed along the route to collect fees from travelers. One tollgate keeper, Perry Vickers, became an integral figure in the history of Mount Hood.

Perry Vickers was among the first residents on the south side of Mount Hood, an area that today includes the small ski town of Government Camp. He was well liked by everyone, especially those passing over the Barlow Road in their wagons.

He secured squatter’s rights at Summit Meadow, a natural clearing at the top of the pass, in 1865. Here, the road began its descent down the west slope of Mount Hood, leading settlers on the final stretch toward the Willamette Valley. Vickers built the first accommodations in the area, including a lodge, store, barns, and a corralled field for livestock.

During his time on Mount Hood, Portland grew rapidly with the influx of new settlers. Many of these settlers returned to the mountain, over the road that had once challenged their or their parent’s journey, seeking recreation and adventure.

Vickers became Mount Hood’s first climbing guide. Hiking and climbing the peak became increasingly popular at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. He enthusiastically promoted visitation and recreation. Vickers even created a tradition of lighting the mountain by carrying fuel for a large fire near what is now known as Illumination Rock. He is credited with being the first person to spend a night atop Mount Hood.

In August 1873, Vickers survived a night on the summit by building a crude rock shelter. Later, he recalled, “I dared not sleep, lest the cold take me. At dawn, I beheld a glory of light such as mortal eyes rarely see.”

Vickers was known as a dreamer and a poet. Newspapers later referred to him as “the mountain’s first true romantic.” The Oregon Historical Society preserves some of his verses about sunrises over the Cascade peaks and sunsets glowing across the summit.

However, his start in Oregon wasn’t on solid footing.

In 1865, Vickers arrived in Vancouver, Washington. While looking for work, he fell in with three other young strangers. Unfortunately, they were soon arrested at Fort Vancouver for horse theft, a serious crime at the time.

They were held for about two months awaiting trial. Each prisoner wore an “Oregon Boot,” a seven-pound iron clevis attached to the ankle to prevent escape. Public sympathy grew for Vickers, who consistently protested his innocence.

Worried that guilt by association would seal his fate, Vickers planned an escape. Their wooden cell allowed them to pry loose several 2″x4″ window bars, and the group fled into the night.

Once free, Vickers separated from his companions. Pursuers closed in as he reached the Columbia River. His ankle was chafed and bleeding from the iron shackle. In desperation, he plunged into the mile-wide, fast-moving river.

Miraculously, he swam across with the seven-pound clevis still attached to his ankle.

On the far bank, Vickers found a farm where he pried off the iron using a wagon wheel wrench and a bolt. The next morning, woodcutters gave him food and directed him to Powell Valley, where his brother lived. His brother provided clothes and supplies and urged him to head east along the Barlow Road to find work until the danger passed.

Traveling east, Vickers met Stephen Coalman, the overseer of the old Barlow Road. Coalman offered him work clearing storm damage from the road, and Vickers accepted. The two men formed a lifelong friendship.

Stephen and his son Elijah “Lige” Coalman would later become legendary for their adventures on Mount Hood. Over time, Coalman became convinced of Vickers’ innocence.

In June, Vickers set up camp at Summit Meadow and explored the area up to the timberline. He swore he would one day reach the mountain’s summit.

At first, Vickers worked as the eastern gatekeeper on the Barlow Road. In time, Coalman convinced him to return to the west side of Mount Hood, promising to help him with legal services if needed.

No charges were ever brought against him.

Vickers loved the Summit Meadow area. He filed a squatter’s claim and started building between his work on the road. In 1866, construction of the Summit House began. The building measured 20x20x32 feet, featuring a huge fireplace, upstairs sleeping quarters, and a large kitchen. Vickers built all the furniture by hand from local materials.

By the spring of 1868, as soon as the snow melted, the Summit House opened for travelers. Vickers provided food and shelter for people and livestock. He often refused payment from settlers who had little to give, earning a reputation for generosity.

In 1882, a tragedy struck Summit Meadow. A baby boy from a wagon party, the Barclay family, became ill and died at the meadow. Vickers granted permission for the boy to be buried there. The grave and headstone still remain today.

Later accounts said that Vickers personally tended the grave, keeping it marked and protected from passing livestock.

For years, Vickers remained at Summit Meadow, aiding travelers and leading hundreds to the summit of Mount Hood. Then, in August of 1883, violence shattered the peace and led to the first Murder on Mount Hood.

A man named Steele, a farmhand near the Columbia Slough, stole a shotgun and fled east. The Multnomah County Sheriff deputized two men, including the gun’s owner, Roarke, to pursue him.

The deputies tracked Steele to Eagle Creek and had their warrant reissued for Clackamas County. They learned that Steele had traded the shotgun for a powerful Sharps rifle.

Despite bad weather, they pressed on through Sandy, stopping only to buy a bottle of whiskey. Reaching the town of Salmon, near today’s Brightwood, they enlisted local trading post owner John McIntyre. One deputy, having fallen ill, returned home. McIntyre was deputized, and the search continued.

At Summit Meadow, Vickers told the men that Steele had stayed the previous night. Vickers warned them that Steele was a dangerous character and advised waiting until morning to pursue him, suggesting they rest and sober up.

Roarke insisted they continue into the night. Vickers, now deputized, reluctantly agreed to lead them.

They reached the White River Trading Post operated by Cornelius Gray. Beyond the buildings, they spotted a campfire.

Concerned about his companions’ condition, Vickers volunteered to approach Steele’s camp alone. As he rode off, he reportedly quipped, “If you hear me shout, don’t mistake it for the wind.”

Vickers rode toward the fire, confirming it was indeed Steele. As he dismounted his horse, Steele seized the Sharps rifle and shot Vickers in the stomach.

Vickers fell but managed to draw his revolver and fire into the darkness. Believing he might have wounded Steele, he emptied his gun but could not stop the fugitive.

Cornelius Gray, hearing the shots, rushed to the scene. He and others found Vickers gravely wounded, struggling to reload his revolver with trembling hands.

Vickers accused the deputies, Roarke and McIntyre, of cowardice, saying they abandoned him when he needed them most. Witnesses later agreed, noting that their horses had not actually bolted, and their retreat seemed deliberate.

A messenger rode to fetch Stephen Coalman, but it was too late. Vickers, lying inside Gray’s cabin, knew his fate.

He mentioned laudanum stored back at his lodge. Gray had nothing in his cabin to relive Vickers’s pain. Vickers acknowledged that no one could help him now. His final request was to be buried next to the Baby Barclay that he helped bury in his beloved Summit Meadow. His final words were reported as, “Tell them I did my best, for the mountain and for the law.”

At 7am, August 19, 1883 Perry Vickers died from his wounds. According to his wishes his body was loaded into a wagon and carried back to Summit Meadow and buried next to the baby.

The Mount Hood community mourned him deeply. Samuel Welch and Stephen Mitchell crafted his coffin, and Oliver Yocum officiated his burial.

Vickers is laid to rest at Summit Meadow, beside the Barclay child he had once shown such compassion toward. Their headstones remain today.

Locals remembered Vickers as “the silent sentinel of Summit Meadow,” honoring his years of guidance, kindness, and service on the mountain.

Soon after Vickers death a “religious eccentric” named Horace Campbell, known as “King David” occupied the Summit House. He rebuilt the Summit House and, behind the structure, constructed a conical shaped wooden teepee with a central fireplace and a smoke hole at the top. It was used by the last wave of immigrants over the old road.

In time, and after many occupiers of the old Summit House, the structure was fell into disrepair and was disassembled and burned on campfires by travelers. First the log furniture and then the structures. Today there’s no evidence that it even existed.

Billy Welch, The son of local rancher Samuel Welch, related a sad story about how Greeley, a yellow Newfoundland and Eskimo dog mix owned by Vickers, refused to leave his master’s grave for days. Finally he and Drum, a spotted hound, also belonging to Vickers, were brought to Welches to live with Samuel Welch, who had been a close friend with Vickers for years. It was necessary to keep a close watch on Greeley for days, because he wanted to return up the Barlow Trail to Summit Meadow where is master was buried.

Stephen Coalman kept Vickers’ blood-stained coveralls for years, hoping they might someday serve as evidence.

Later, a horse thief hanged in eastern Oregon claimed to have killed a man in the Cascade Mountains. It was widely assumed this was Steele.

Coalman, realizing the case had ended, eventually burned Vickers’ coveralls. Thus ended the story of Mount Hood’s first murder—and the enduring legend of Perry Vickers.

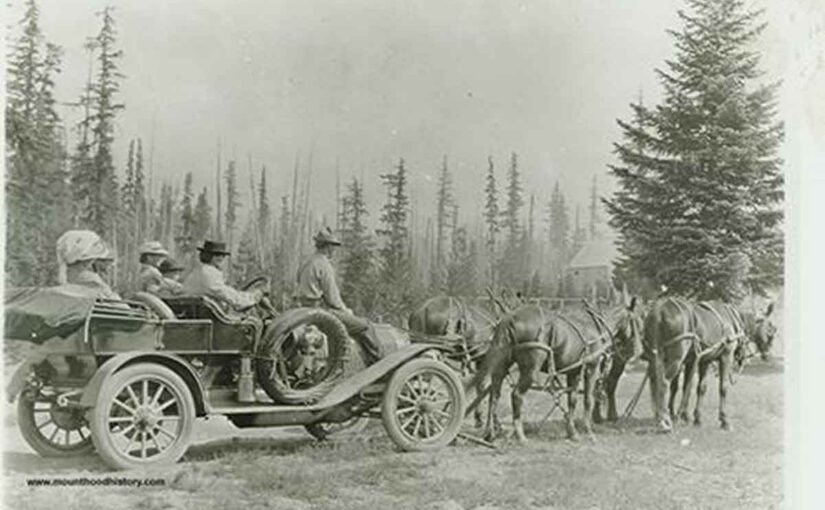

Four Horsepower.

An early automobile pulls in to Government Camp, Oregon under auxiliary power.

Protest at Timberline Lodge – Unfair to skiers.

Timberline Lodge ‘s first Winter was a rocky one business wise.

“From W. P. Gray

The News-Telegram

Portland, Oregon

12-23-1937

Two months after its dedication by President Roosevelt, Timberline Lodge on Mt. Hood, Oregon, $650,000 structure built with WPA money, was picketed by skiers who demanded immediate opening of the lodge’s sanitary facilities to skiers. No operator has been found for the massive Alpine hostelry, and “keep out” signs bar all doors. A corporation of Portland business men is reportedly forming to open the lodge. The picketing skier above is Ken Soult.”

#oregon #oregonhistory #timberlinelodge #mthoodhistory #mounthoodhistory