When Live Bears Entertained Tourists

Bears Were Once a Common Sight at Government Camp

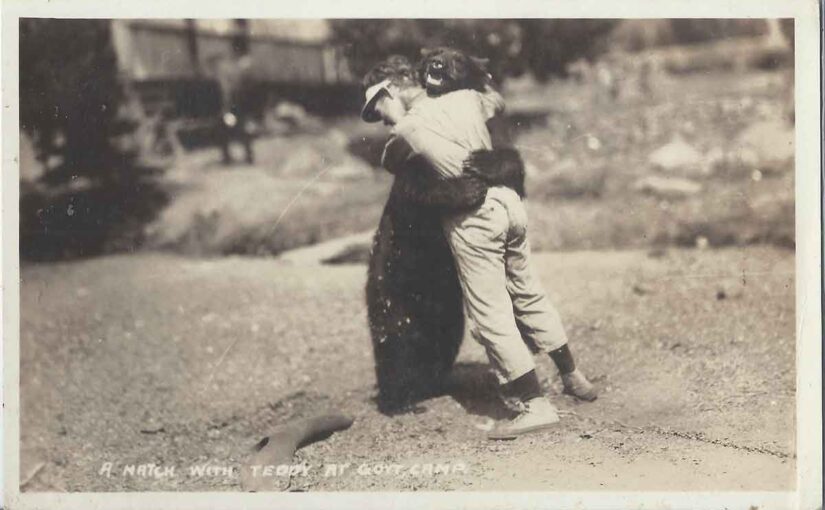

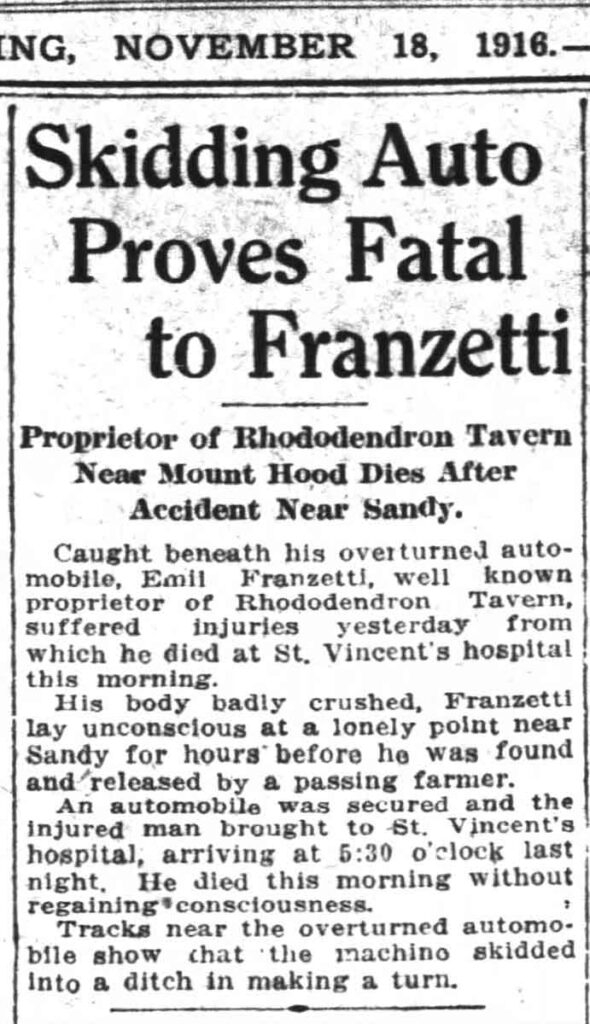

In the 1920s and ’30s, tourists came to Mount Hood for snow, scenery, and rustic lodging. But for a short time, they also came to see the Government Camp bears.

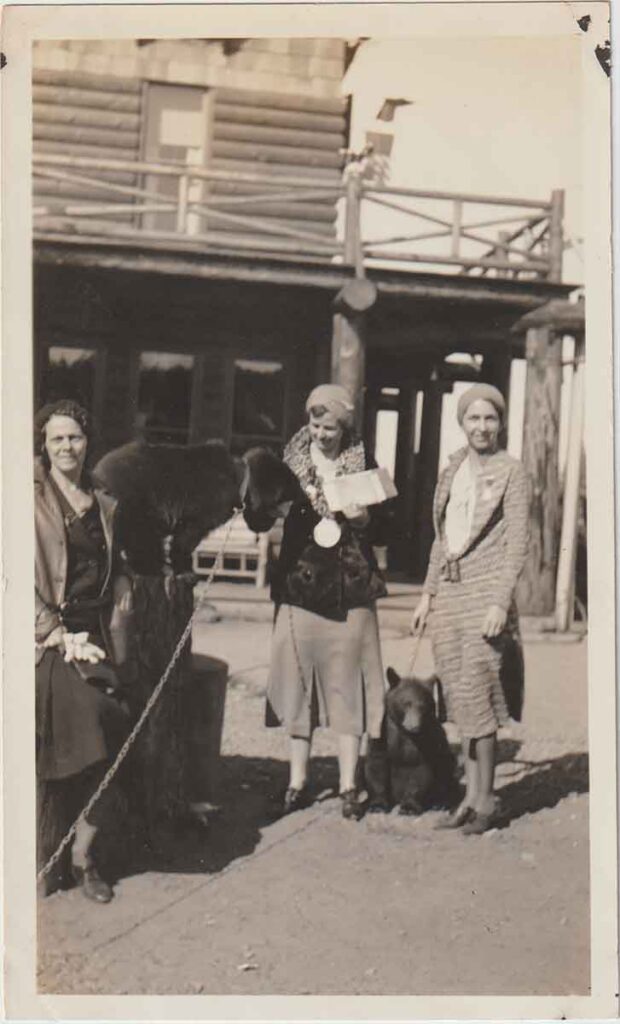

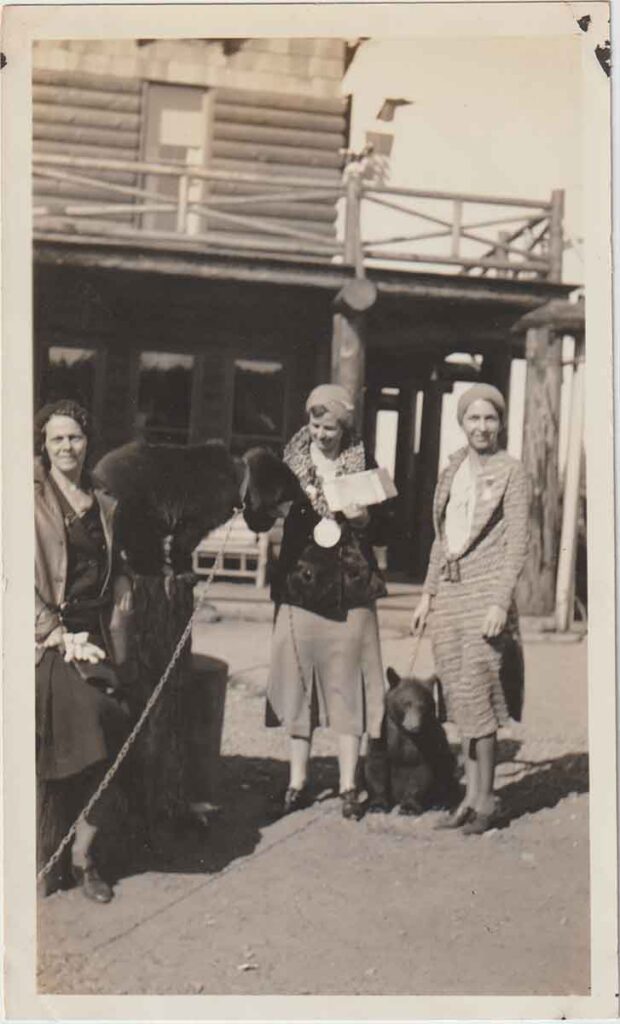

Lodges in Government Camp kept live bear cubs on-site. These animals, often orphaned, were raised by hand and used as attractions. Visitors watched them, fed them treats, and sometimes posed for photos. Today, that might sound outrageous—but back then, it was a novelty.

Keeping bears on chains wasn’t unique to Mount Hood. From East Coast resorts to Western roadside stops, bears often entertained guests. Government Camp followed the same trend.

The Setting: Government Camp in the Early Days

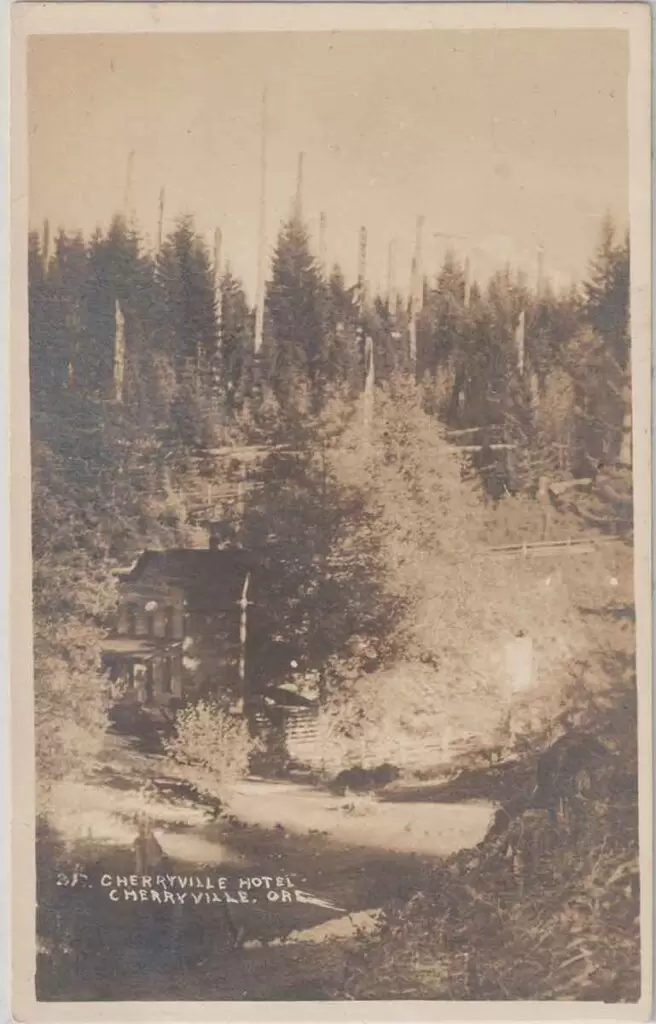

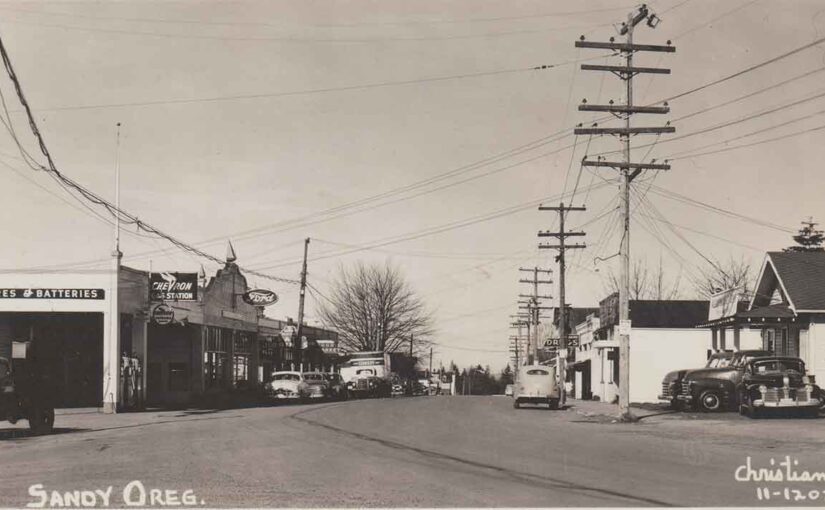

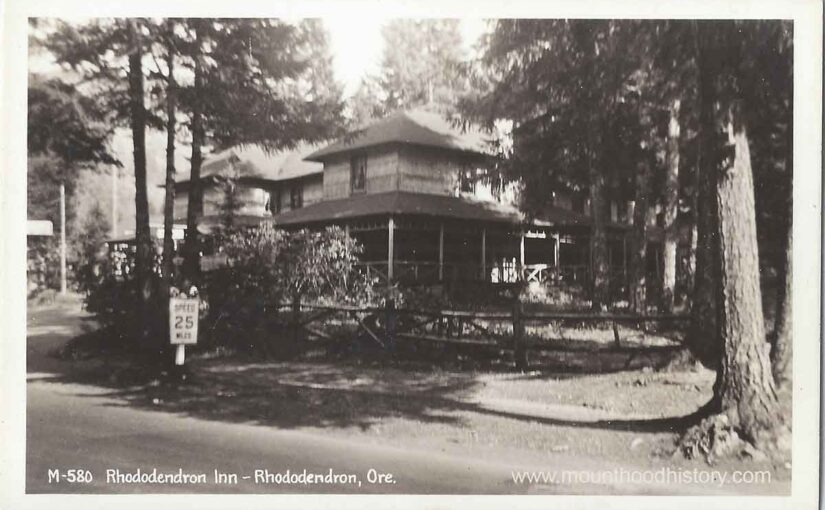

Government Camp began as a U.S. Cavalry supply cache along the Barlow Road in 1849. By the 1920s, it had grown into a seasonal hub for outdoor recreation. The new Mount Hood Loop Highway brought more visitors, and businesses expanded to meet demand.

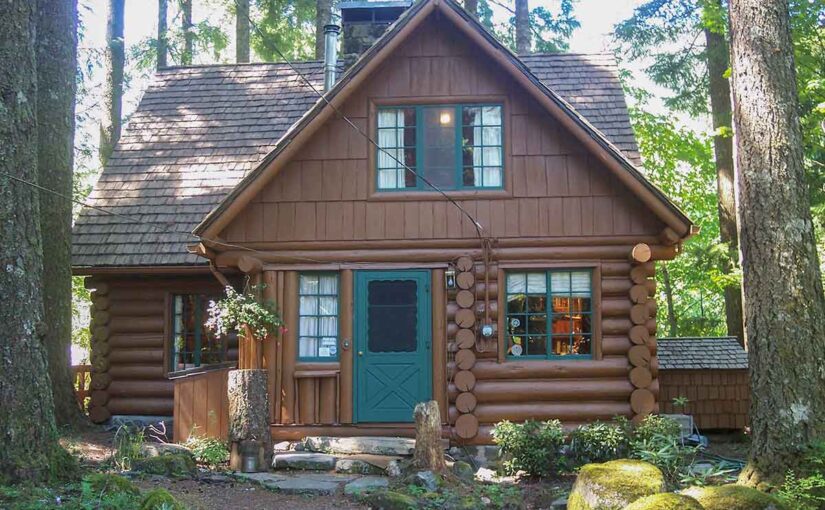

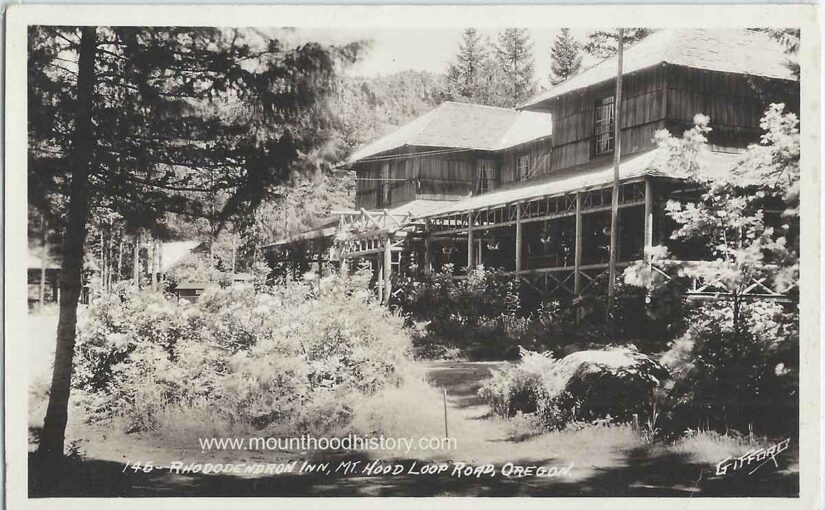

The town had cozy lodges, a general store, a blacksmith, and rugged charm. Two of the most popular stops were the Government Camp Hotel and the Battle Axe Inn. These places offered a mix of alpine hospitality—and bears.

A Runaway Bear and a Snowy Chase

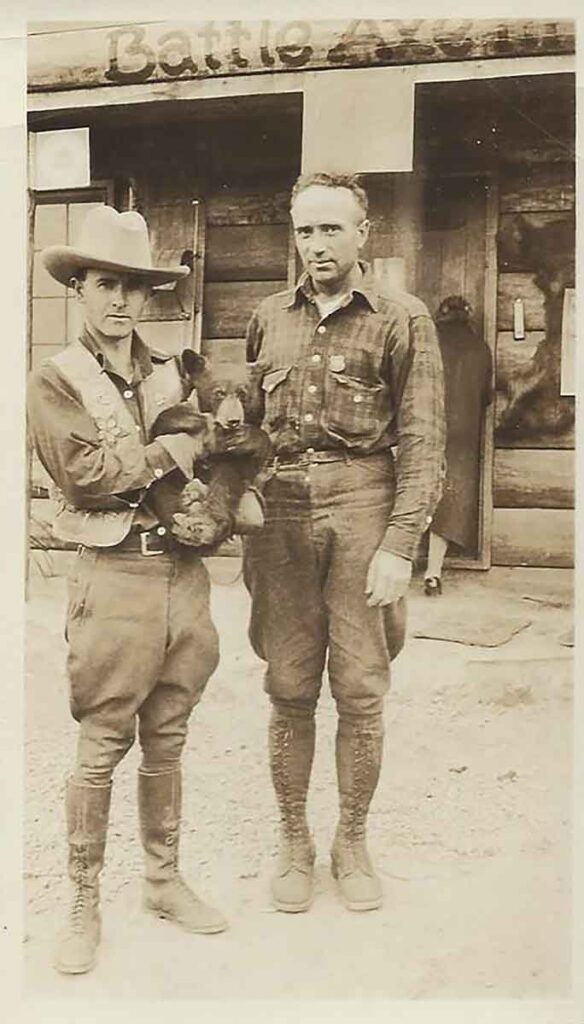

In January 1927, a full-grown, unnamed bear escaped from the Battle Axe Inn. The bear, owned by innkeeper E.J. Sickler, broke free from its chain and ran into the woods. Guests and locals tried to catch it, chasing it through the deep snow.

Bill Lenz, a veteran mountaineer, finally ended the chase. He roped the bear and calmly led it back to its enclosure. Newspapers described the event as an unexpected winter adventure. It was the kind of thing that could only happen on Mount Hood.

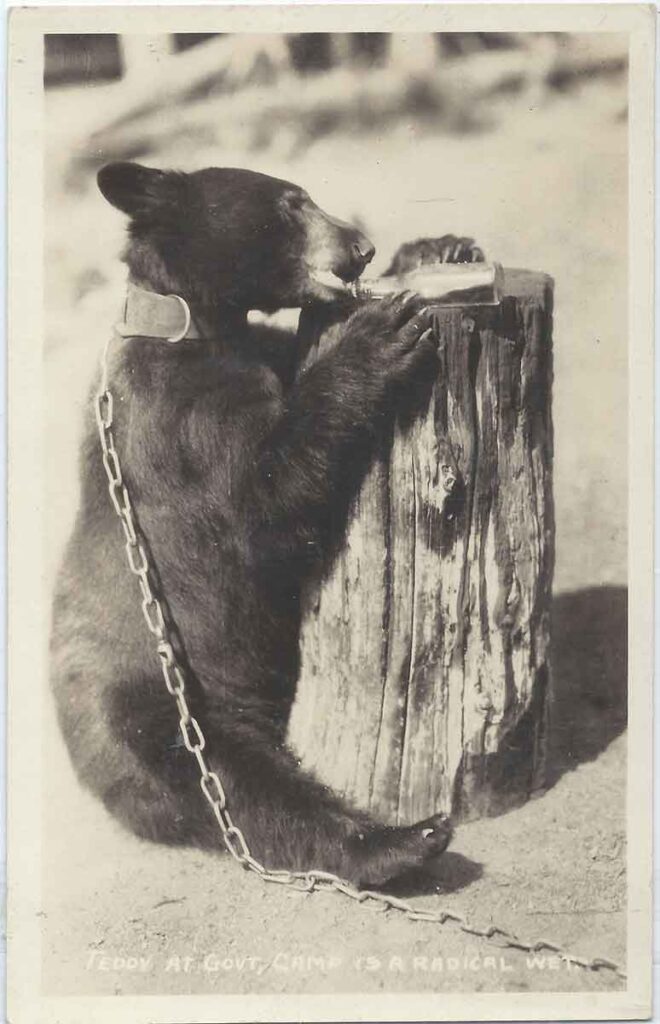

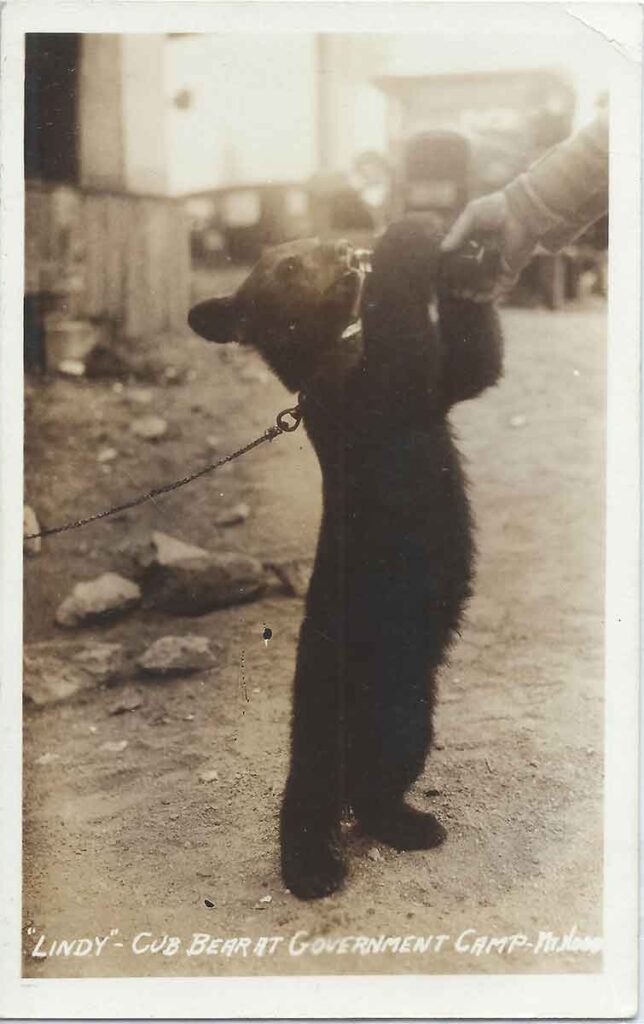

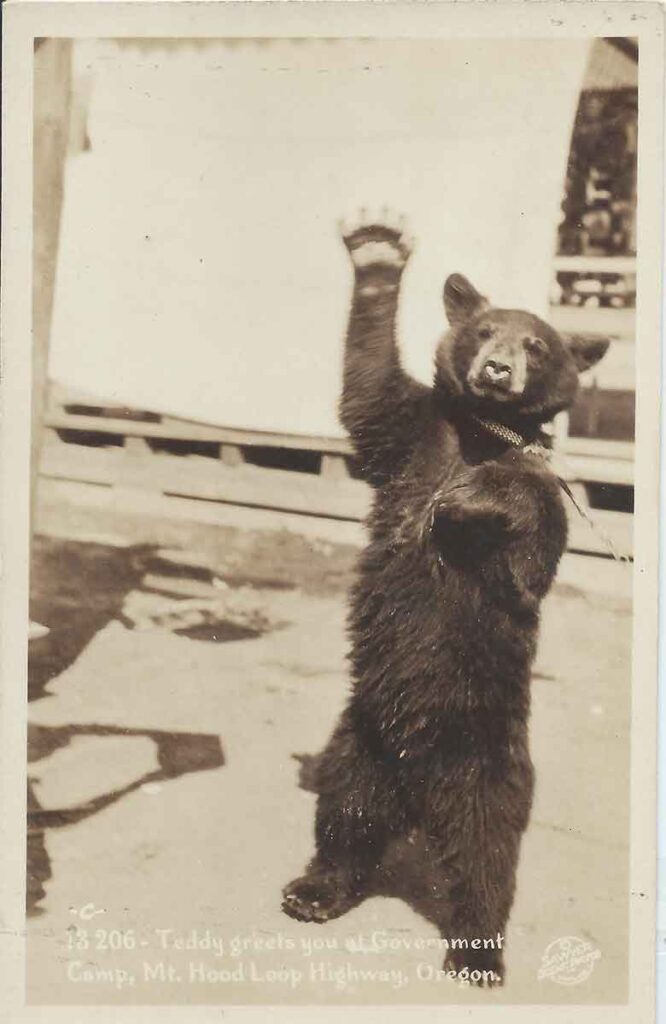

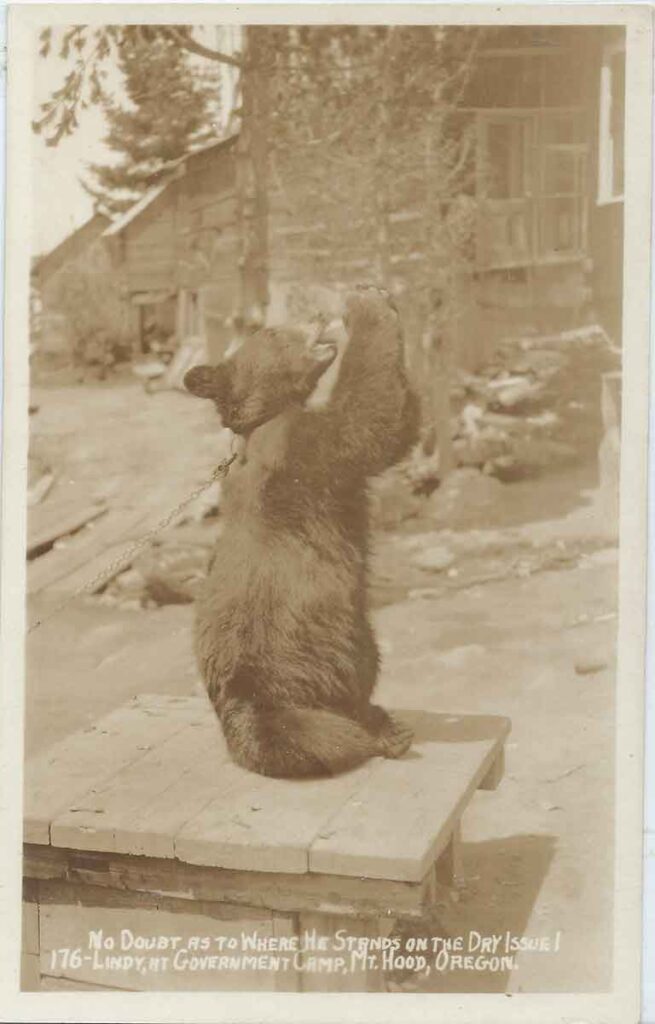

Teddy, Then Lindy—and Others

Of all the bears once kept at Government Camp, only two became widely known—Teddy and Lindy. They appeared on postcards, in newspapers, and in the memories of mountain visitors. But they probably weren’t the only bears that lived there.

Teddy was the first. In the mid-1920s, he lived at the Government Camp Hotel. Trained to do tricks and drink soda pop, he became a tourist favorite. People gave him candy and snacks. He entertained visitors, but the treats made him sick and harder to control.

Eventually, Teddy grew too large and unpredictable. The hotel owner put him down.

They soon bought a new cub—Lindy. She was named after Charles Lindbergh, whose famous flight made headlines in 1927. The hotel hoped she would carry on Teddy’s role as a mascot. But Lindy never learned the same tricks. She had just begun drinking soda from bottles when she also became unmanageable.

Given how common it was in that era to take in orphaned cubs, it’s likely that other bears came and went from the lodges in Government Camp without fanfare. Teddy and Lindy became the best known simply because they were the ones who happened to become the most famous.

Trouble Inside the Hotel

In 1929, a newspaper article reported that both Lindy had damaged property inside the Government Camp Hotel. That incident marked the end of Lindy. Hotel staff euthanized the bear. It was a quiet ending—reported without drama, but with finality.

By then, attitudes were starting to shift. More people were beginning to understand that wild animals, even if raised by hand, don’t belong in hotels.

A Bear for the Movies

At least one bear from Government Camp ended up in a film. In 1927, a movie crew shooting on Mount Hood purchased onr of the pet bears. The idea of selling a bear to Hollywood might seem odd now, but back then it was business as usual.

The Practice Continued Into the 1930s

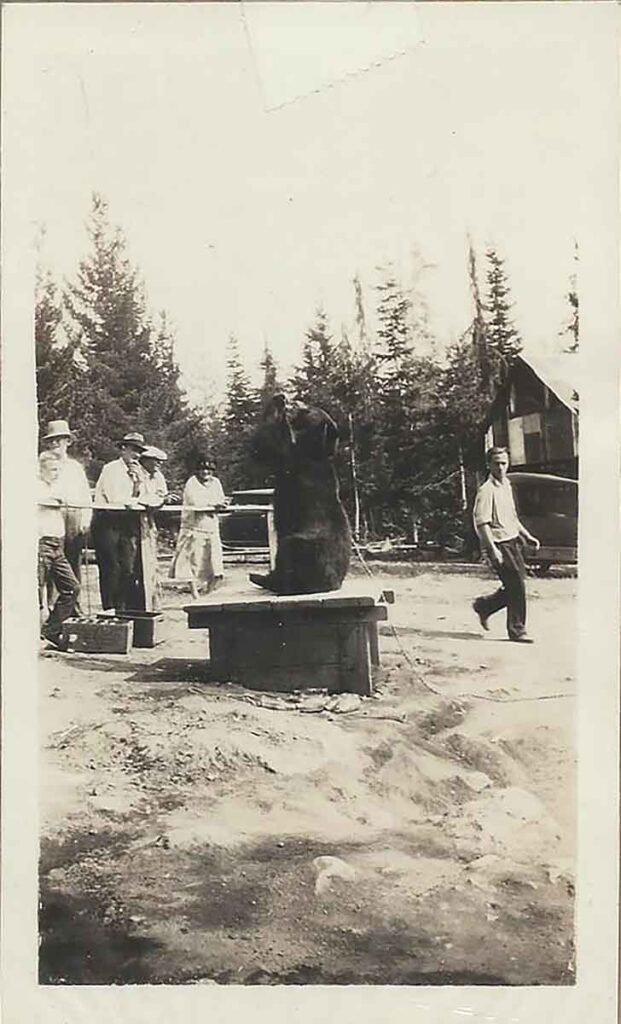

Some assume the practice ended with Teddy and Lindy. But a photo in my collection tells a different story. Dated October 31, 1937, the image shows a penned bear in Government Camp. A wooden sign above the enclosure simply says “Bear.”

The fencing is made of logs and wire. A tire toy hangs inside the pen. This shows that bears remained part of the tourist scene at Government Camp even a decade after Teddy’s arrival.

Government Camp Bears: A Lasting Impression

Over the years, I’ve collected many historic photos of these animals. One shows Lindy drinking from a soda bottle. Another captures Teddy on a tree stump. A third shows a cub in front of the Battle Axe Inn. These images offer a glimpse into a time when the line between wild and tame was much thinner.

The Government Camp bears are remembered with a mix of amusement and discomfort. Their stories reveal a strange chapter in Mount Hood’s past—one where animals were both beloved and exploited.

Today, bears live freely in the forests around Mount Hood, as they should. But for a brief moment in history, they were part of the welcome party.