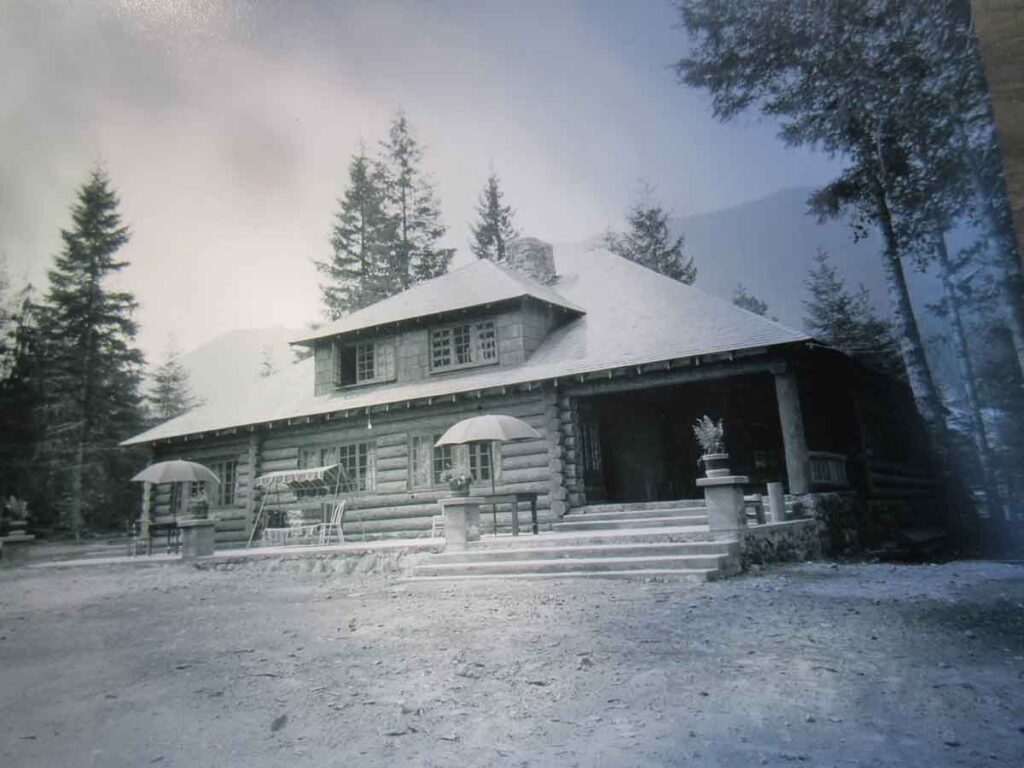

When Live Bears Entertained Tourists Pet Bears Were Once a Common Sight at Government Camp In the 1920s and ’30s, tourists came to Mount Hood for snow, scenery, and rustic lodging. But for a short time, they also came to see the Government Camp bears. Lodges in Government Camp kept live bear cubs on-site. These … Continue reading Government Camp Bears: Mount Hood’s Forgotten Mascots

Tag: oregon history

Curtains in the Forest: Rhododendron Summer Theater

A Mountain Legacy Remembered A Cultural Bloom in the Heart of the Forest Just east of Portland, along the winding curves of Highway 26, sits Rhododendron, Oregon—a place not quite a town, but more than a roadside stop. Nestled in the folds of the Mount Hood National Forest, it’s a patchwork of tall trees, weathered … Continue reading Curtains in the Forest: Rhododendron Summer Theater

Scandal in Cherryville: The Man Who Guarded a Grave

In the summer of 1911, the Friel case in Cherryville Oregon became one of the most disturbing stories ever told from the Mount Hood foothills. A suspicious death, a hurried marriage, a missing medicine bottle, and an armed grave watch pushed a grieving family to the brink of collapse.

Nettie Connett: The Woman Who Became a Legend

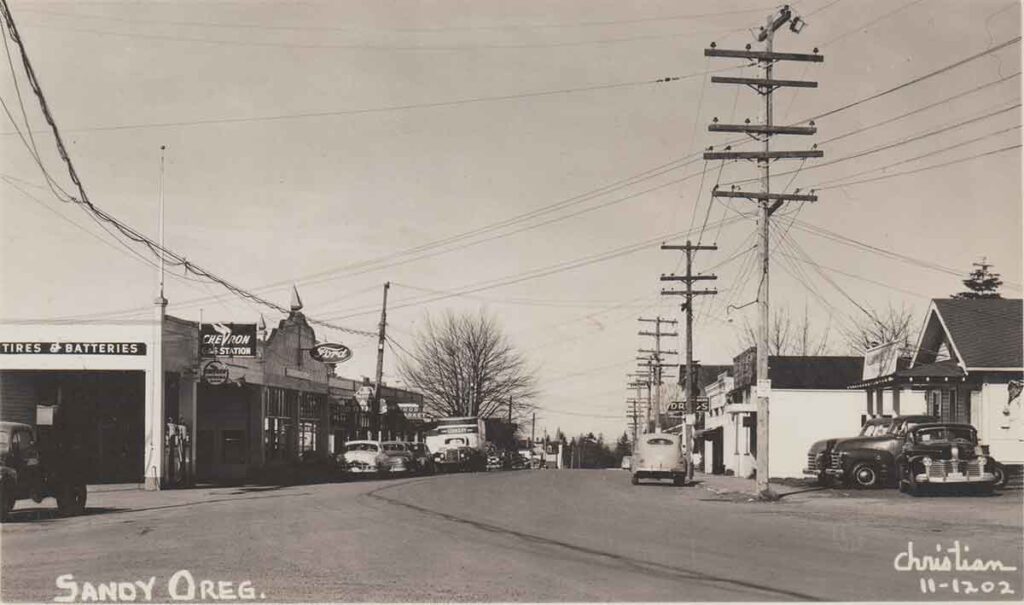

In the timbered hills near Sandy, Oregon, few names live on like Nettie Connett. Born March 5, 1880, in Independence, Oregon, Nettie Loraine Connett would grow into one of the most unforgettable figures in Clackamas County history.

The Legendary Mrs. Pierce: She Killed a Bear With Her Hoe

I’ve spent a lot of time talking with old-timers and the family members of folks who’ve lived up here in the Mountain Community for years. In one or two conversations, I’d heard tell of a woman who gained local notoriety for killing a bear that invaded her space with a garden hoe.