Billy Welch: The Heart and Soul of Welches, Oregon

A Young Pioneer – Billy Welch Welches Oregon

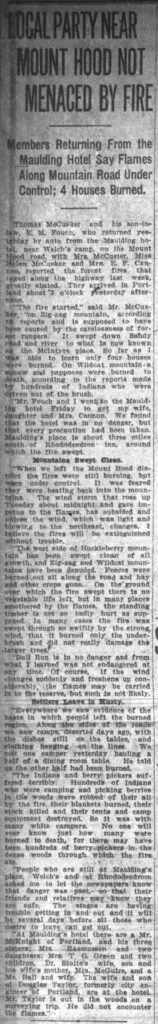

Billy Welch Welches Oregon – In the shadow of Mount Hood, where the Salmon River winds through a valley rich in history, the legacy of William “Billy” Welch remains deeply embedded in the land he called home. Billy Welch was more than just a homesteader — he was a community builder, a businessman, and a generous soul whose efforts helped shape the town that bears his family name.

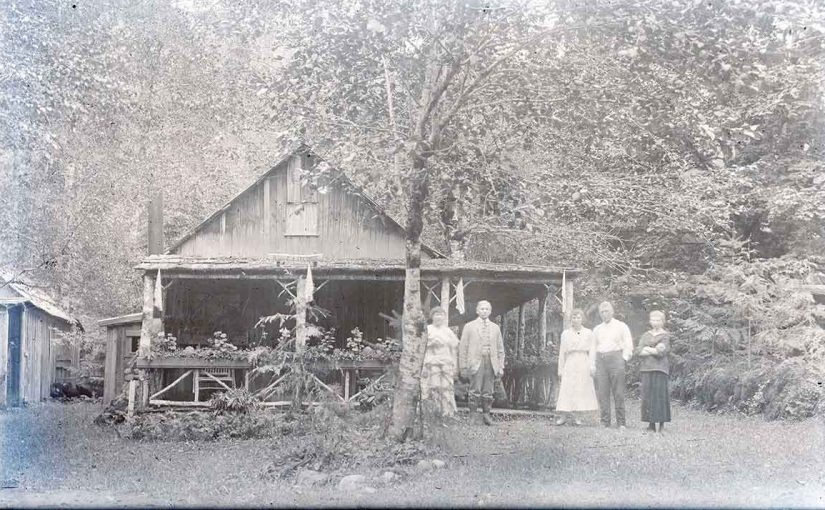

Billy Welch was born on December 24, 1866. At the age of 16, he moved with his father, Samuel “Uncle Sam” Welch, to the Salmon River Valley. In 1882, they each claimed 160 acres of land and built a homestead. Over time, their property expanded to 1,000 acres.

Life on the Welch Ranch

The Welch ranch was a self-sufficient farm with pastures, barns, livestock, orchards, and a vegetable garden. Moreover, the nearby hills provided ample game. In addition, the Salmon River, which runs through the land, was teeming with fish. Billy continued to run the property as a ranch. Billy married Mamie Kopper in 1902 but Mamie died in 1903. Their daughter Lutie “Welch” Bailey was a resident of the area until her death.

Building a Community

Billy cared deeply about the growing settlement. In 1886, with neighbor Firmer Walkley, he claimed a one-acre plot at the junction of the Barlow Road and the road to Welches. They used this land to build the first Welches School. As a result, this early investment in education showed Billy’s dedication to the families establishing roots in the valley.

After Samuel’s death in 1889, Billy inherited the land and continued to develop the property. Not long after, tourists seeking respite from the city began arriving. Therefore, Billy responded by adapting the ranch to welcome them.

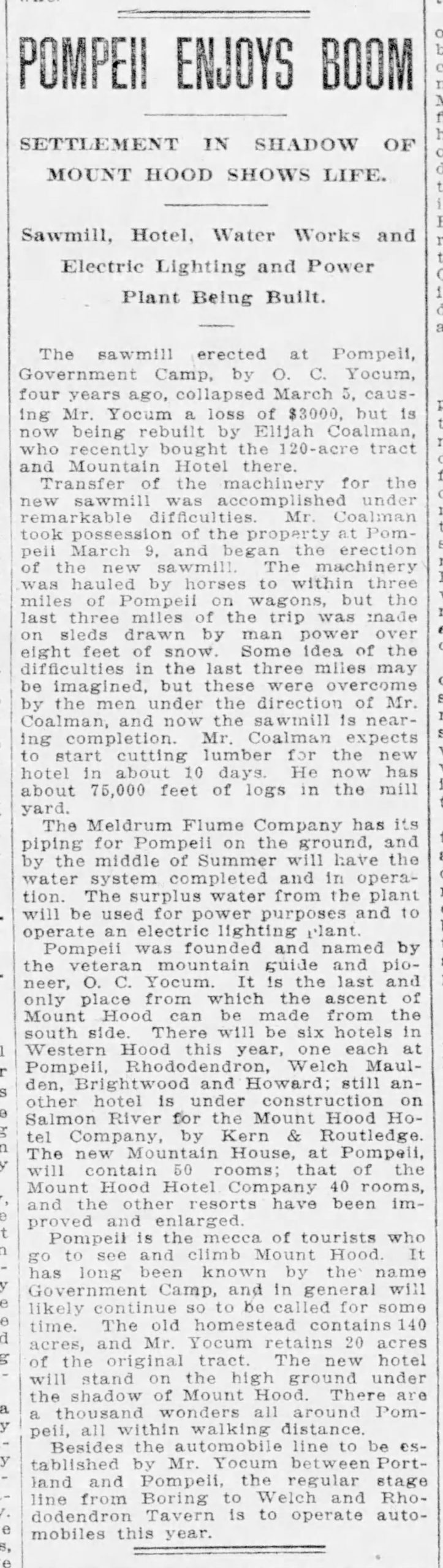

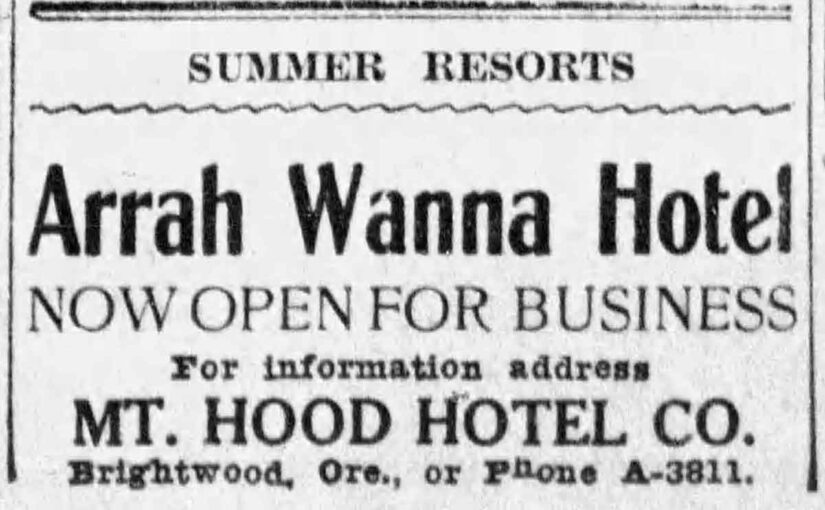

Welches Becomes a Destination

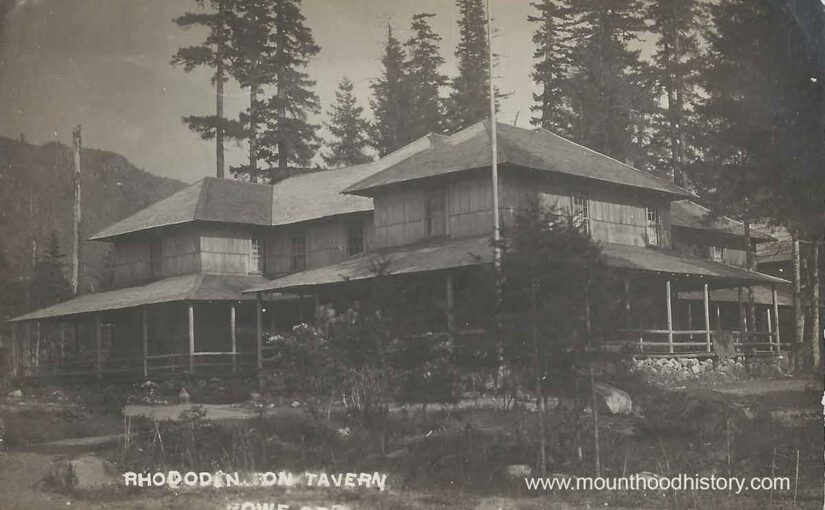

By 1905, the property was leased to Clinton “Linny” Kern and a Mr. Wrenn as a hotel resort. To keep up with demand of the tourists that were coming, Billy expanded the facilities. He added a dining hall, a dance hall, a store and a post office near the Welches Hotel. As demand increased, he also added tent cabins throughout the area. Billy took the hotel and property back from Kern and Wrenn in 1909.

In addition to running the resort, Billy remained focused on the growing community. In fact, he often supported neighbors and welcomed guests, making the Welch homestead a hub of local life. Furthermore, his hospitality created lasting memories for the many visitors who lived there or those who passed through.

A Life Full of Laughter and Music

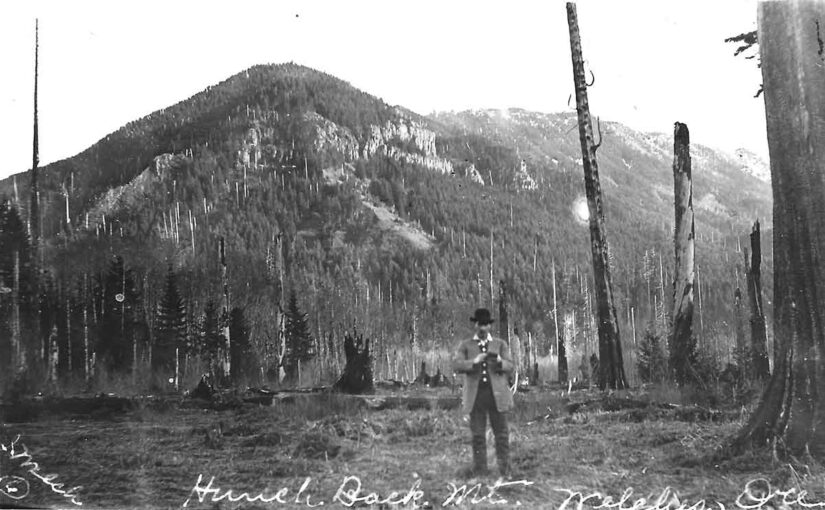

People remember Billy as a jolly soul — good-natured, generous, and full of humor. He played the fiddle and hosted Saturday night dances that would sometimes last through the night, which were popular with both locals and visitors. These lively events took place in the dance hall above his store. There are stories told how the whole building seemed to rock while everyone danced to Billy and his fiddle and the occasional volunteer on the piano. The hall had an east-facing balcony. From there, guests cooled off and enjoyed moonlit views of Hunchback Mountain.

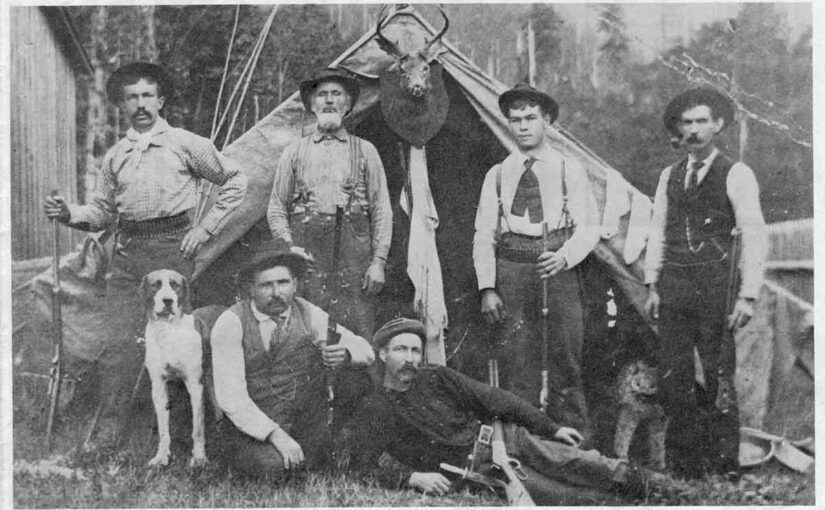

Billy also loved the outdoors. He was an avid hunter who relied on his hounds to flush out deer. Notably, his favorite dog, Leader, was a loyal companion on many trips. It’s common to see his dog next to him in photos. Whether he was playing music, greeting visitors, or roaming the forest with his dogs, Billy lived life with energy and joy.

A Strong Partnership

In April 1911, Billy married Jennie Faubion. She was the daughter of local homesteaders William and Anna Faubion. Together, Billy and Jennie managed the resort, store, post office, and dance hall. Jennie played a vital role in the operation and success of their ventures.

As Welches attracted more visitors, Billy began selling small plots of land to regular campers. Consequently, these families built summer cabins and returned year after year. This trend marked the beginning of Welches as a seasonal destination for recreation and relaxation that still exists today.

Over time, the town grew. Thanks to the couple’s efforts, Welches developed a strong reputation as a friendly, welcoming place. It became a destination loved by visitors and settlers alike. In many ways, their teamwork laid the foundation for the community spirit that still exists today.

Leaving a Legacy

In 1928, Billy leased part of his land to Ralph Waale, who constructed a nine-hole golf course and operated it until 1939. Eventually, after Waale stepped away, Billy and Jennie resumed control and managed the golf course until 1942.

Billy also served as the first postmaster of Welches, from 1905 until 1940. Through his service, he helped the growing community stay connected with the wider world. His work laid the foundation for the town’s lasting success. Additionally, after Billy passed, Jennie continued in this role until 1960. Her contributions further strengthened the continuity and spirit of the town.

A Lasting Memory

Billy Welch passed away on October 30, 1942. The land he helped develop eventually became a resort featuring a world-class golf course with sweeping views in all directions. Today, it remains a popular destination that continues to welcome visitors. Now known as The Mt. Hood Resort, it still sits in the same scenic valley that Billy and his father once called home.

Even though the cedar shake cabins and dance halls have almost faded, Billy’s name and spirit live on in Welches. He was more than a pioneer — he was the heart and soul of a community that still thrives in the shadow of Mount Hood.

Ultimately, Billy Welch’s legacy is one of vision, opportunity, connection, and joy. It serves as a reminder that one person’s dedication can shape an entire region for generations to come.