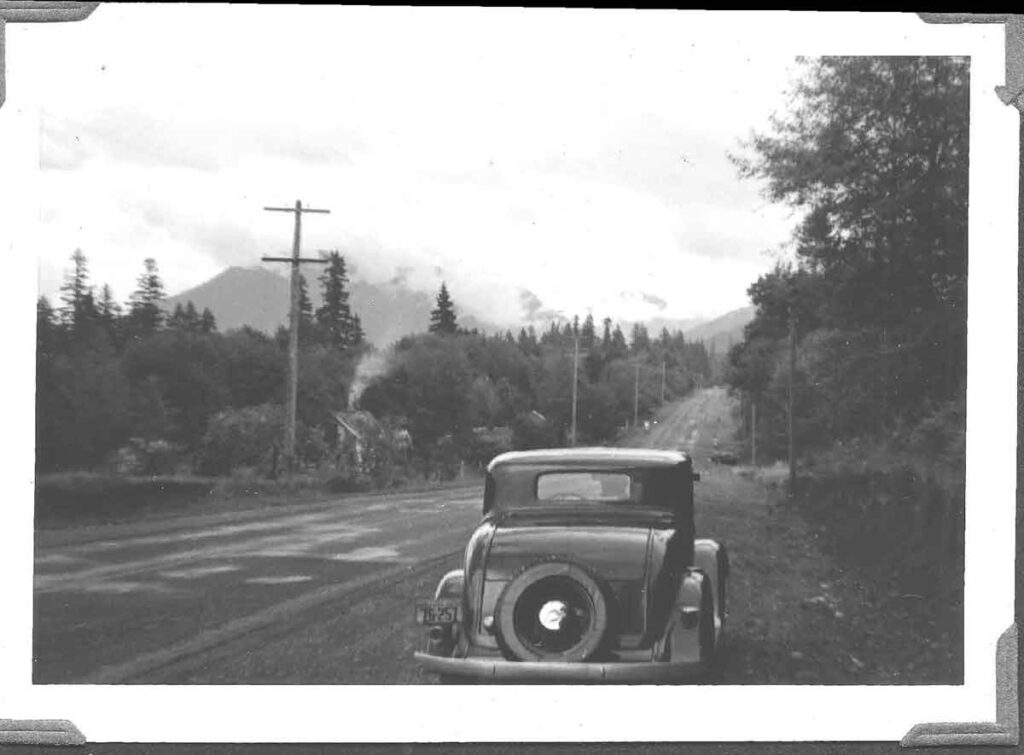

Alder Creek is a little town half way between Sandy and Welches Oregon on today’s Highway 26.

Samuel Welch 1880 Welches Pioneer

Samuel Welch left Virginia and traveled to Oregon via the old Oregon Trail in 1842. In 1882 he and his son Billy each homesteaded 160 acres apiece

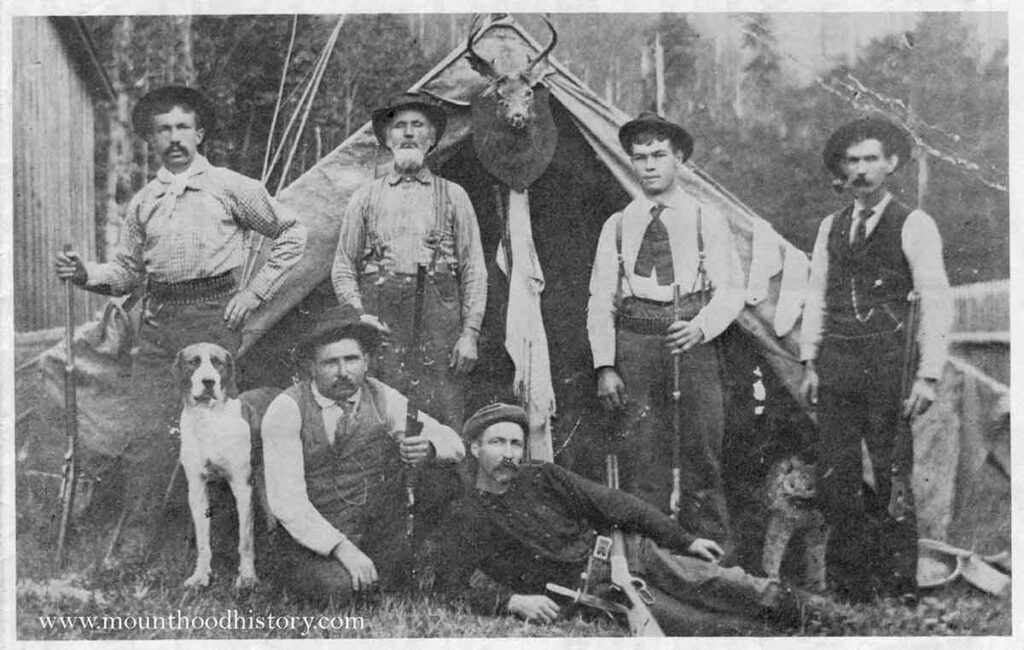

Welches Oregon Pioneer Homesteaders

A photo of the first Welches Oregon pioneer homesteaders.

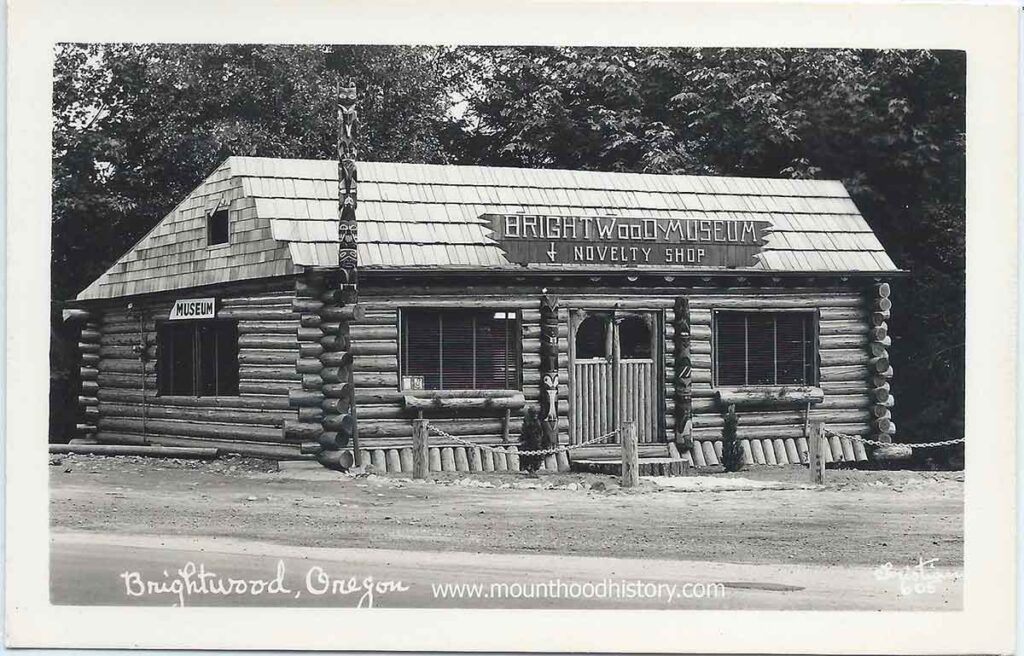

Brightwood Museum and Novelty Shop: Mt Hood Loop History

The Brightwood Museum and Novelty Shop. Many locals who remember this place in its heyday still call this the Snake Pit. In its lifetime it was several things, including a home.

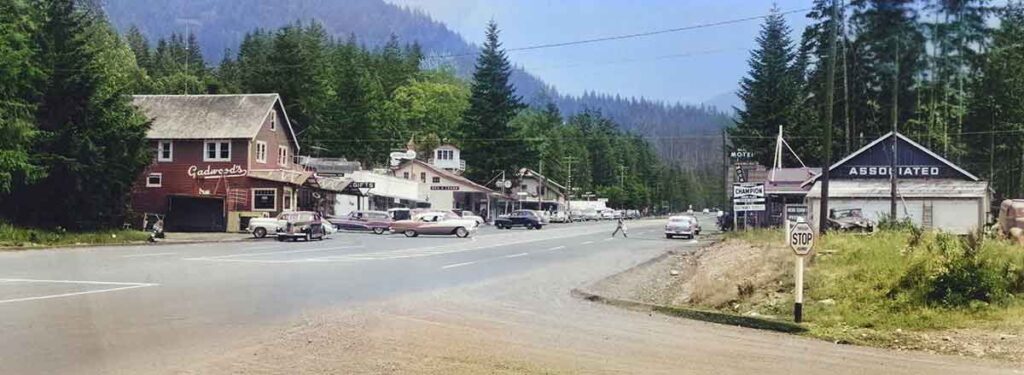

Rhododendron Oregon Centennial and History

a video to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the little Mount Hood village of Rhododendron Oregon.