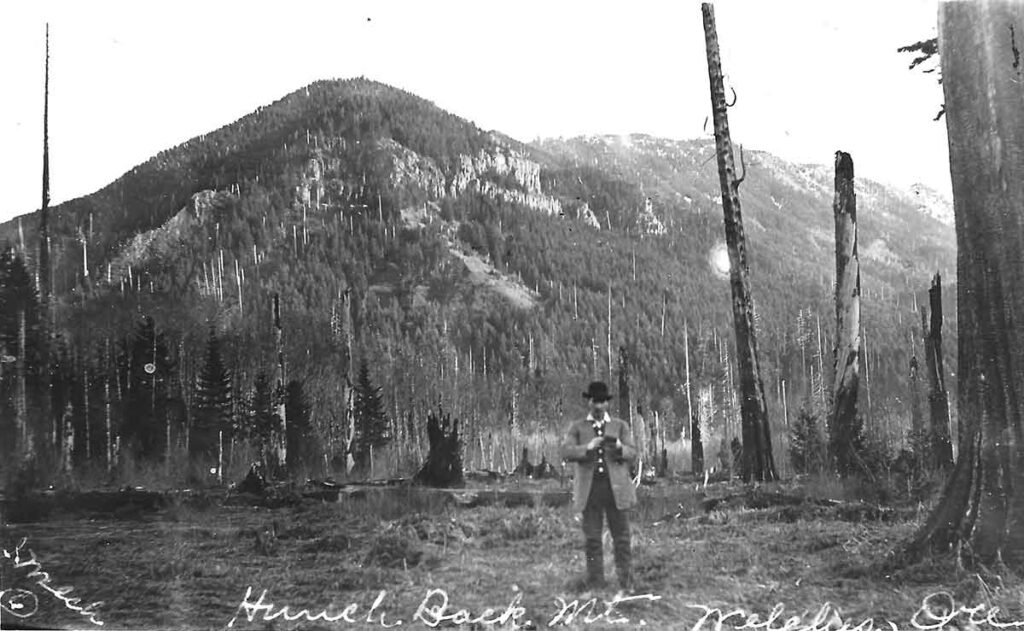

The Burnt Lake Fire of 1904 swept through this area, leaving damage so severe that the lake was named for it. Though the forest has mostly grown back, signs of that fire still linger, more than 120 years later.

Baby Morgan’s Grave: A Tragic Pioneer Story at Summit Meadow

Tucked in the peaceful meadow near Government Camp, Oregon, lies a quiet grave that tells a heartbreaking story. Baby Morgan’s grave is marked by a small bronze plaque mounted on a random boulder named Chimney Rock

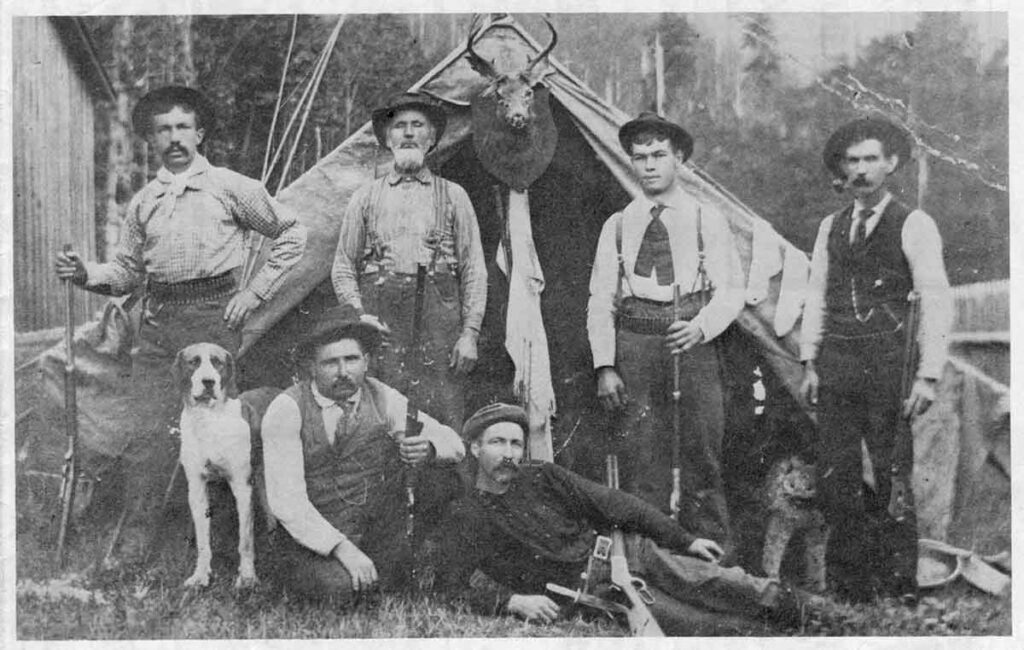

Billy Welch Welches Oregon

In the shadow of Mount Hood, where the Salmon River winds through a valley rich in history, the legacy of William “Billy” Welch remains

Mount Hood Forest Fires of 1910

The Big Burn, or as it was called, “The Big Blowup” saw huge fires in the whole of the Northwest including Idaho, Montana and Washington. Although it wasn’t considered a part of the Big Blowup, that August a wildfire threatened to burn down the towns between Sandy and Government Camp.

Map Curve, Is it Natural, or Man Made?

Map Turn is the sweeping curve located west of Government Camp — just downslope from the new truck escape ramp — where several persons have perished in auto accidents in recent years.