Eyewitness Report from The 1910 Oregon Daily Journal

1910 was a tragic year for forest fires

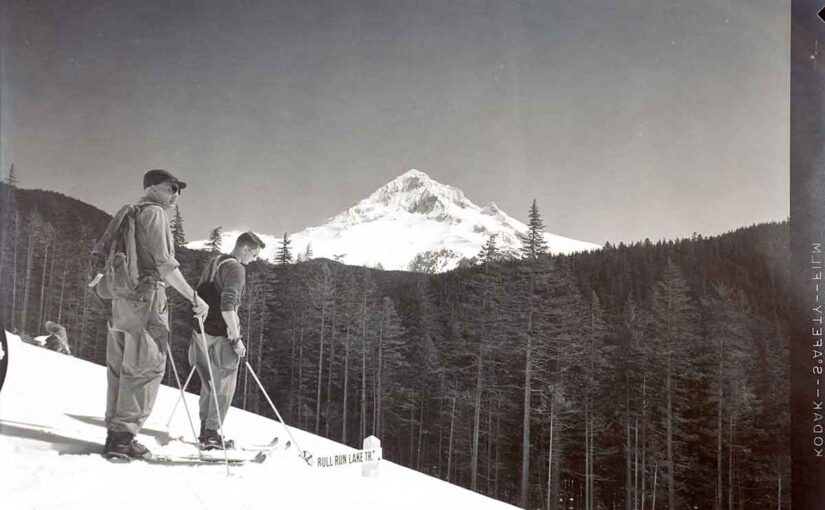

Mt Hood Forest Fires of 1910 – The summer of 1910 brought devastating forest fires to the Mount Hood area, with flames sweeping across Zigzag Mountain, Huckleberry Mountain, Wildcat Mountain, and the surrounding ridges. This firsthand account from the Portland Oregon Daily Journal, published on August 28, 1910, gives us a rare look into the chaos and hardship faced by locals, vacationers, and especially the Indigenous berry pickers during that tragic event.

“The Indians and berry pickers suffered terribly. Hundreds of Indians who were camping and picking berries in the woods were robbed of their all by the fire, their blankets burned, their stock killed and their tents and camp equipment destroyed. So it was with many white campers. No one will ever know just how many burned to death, for there may have been hundreds of berry pickers in the dense woods through which the fire ate.

As someone who has explored and photographed this very landscape, it’s sobering to read how much of a conflagration this fire was and how many people lost their lives. While some of the places mentioned — like the Maulding Hotel and Rhododendron Inn — are now long gone or forgotten, this report captures a moment in time when fire was an ever-present threat in the Oregon woods. A fact that we, in this modern time, seem to ignore until it’s an immediate threat to us.

Read the following about the tragic Mt Hood Forest Fires of 1910

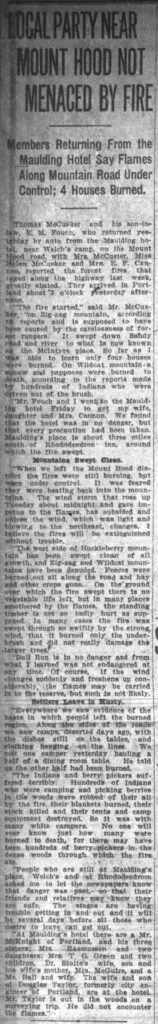

Original Article: The Portland Oregon Daily Journal, August 28, 1910

LOCAL PARTY NEAR MOUNT HOOD NOT MENACED BY FIRE

Members Returning From the Maulding Hotel Say Flames Along Mountain Road Under Control; 4 Houses Burned

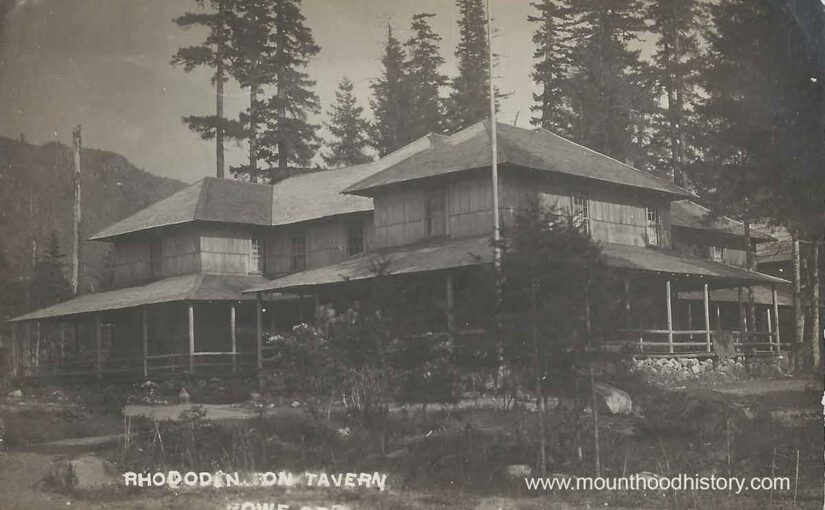

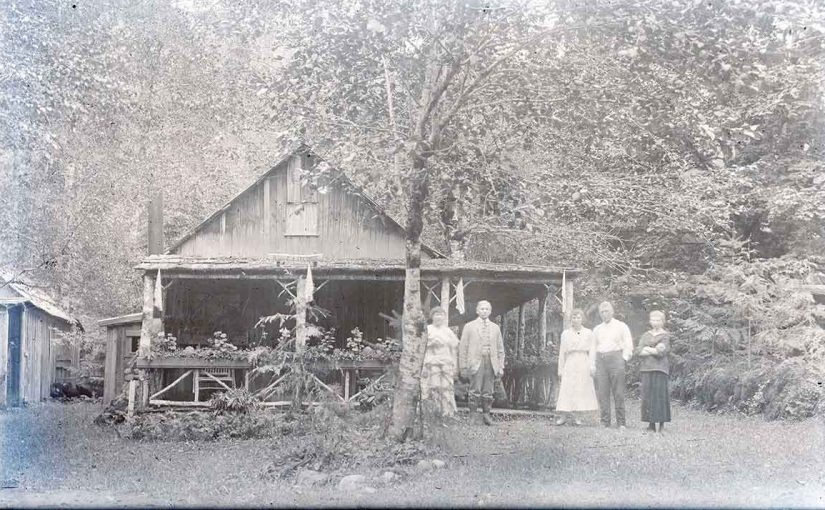

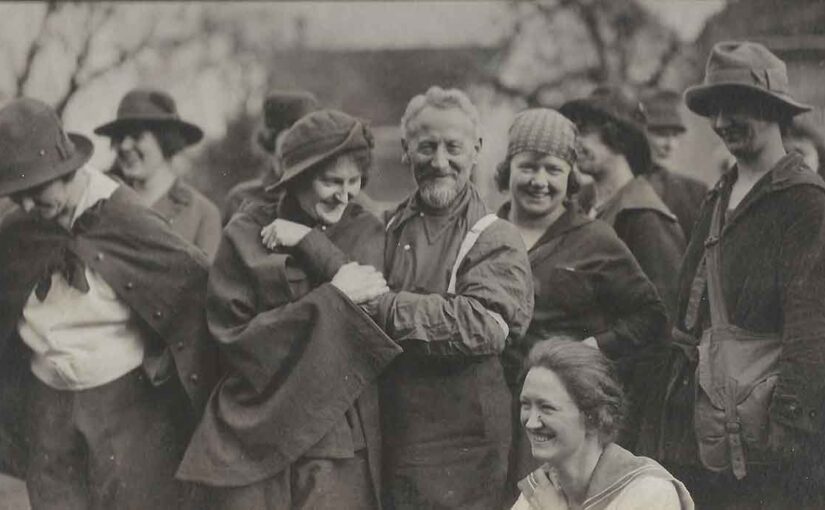

Thomas McCusker and his son-in-law, E.M. Fauch, who returned yesterday by auto from the Maulding hotel, near Welch’s camp, on the Mount Hood road, with Mrs. Custer, Miss Helen McCusker and Mrs. E.F. Cannon, reported the forest fires that raged along the highway last week, greatly abated. They arrived in Portland about 3 o’clock yesterday afternoon.

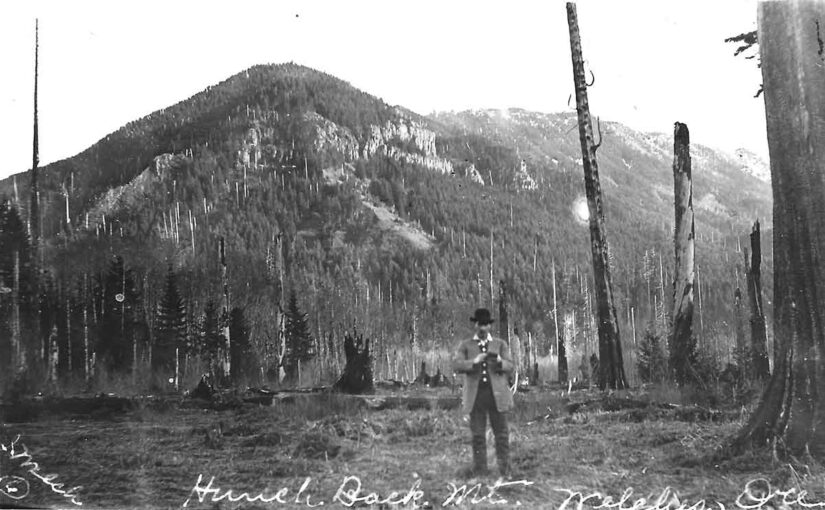

“The fire started,” said Mr. McCusker, on Zig-zag mountain, according to reports and is supposed to have been caused by the carelessness of forest rangers. It swept down the Sandy road and river to what is now known as the McIntyre place. So far as I was able to learn only four houses were burned. On Wildcat mountain a squaw and pappoose were burned to death, according to the reports made by hundreds of Indians who were driven out of the brush.

“Mr. Fouch and I went to the Maulding hotel Friday to get my wife and daughter and Mrs. Cannon. We found that the hotel was in no danger, but that every precaution had been taken. Maulding’s place is about three miles south of Rhododendron inn around which the fire swept.

Mountains Swept Clean

“When we left the Mount Hood district the fires were still burning, but were under control. It was feared they were beating back into the mountains. The wind storm that rose up Tuesday about midnight and gave impetus to the flames, has subsided and unless the wind, which was light and blowing to the northeast, changes, I believe the fires will be extinguished without trouble.

“The west side of Huckleberry mountain has been swept clean of all growth, and Zig-zag and Wildcat mountains have been denuded. Fences were burned out all along the road and hay and other crops gone. On the ground over which the fire swept there is no vegetable life left, but in many places smothered by flames, the standing timber is not so badly hurt as supposed. In many cases the fire was swept through so swiftly by the strong wind, that it burned only the underbrush and did not really damage the larger trees.

“Bull Run is in no danger and from what I learned has not been endangered at any time. Of course, if the wind changes suddenly and freshens up considerably, the flames may be carried into the reserve, but such is not likely.

Settlers Leave in Hurry

“Everywhere we saw evidence of the haste in which people left the burned region. Along the sides of the roads we saw camps, deserted days ago, with the dishes still on tables, and clothing hanging on the lines. We met one camper yesterday hauling a half of a dining room table. He told us that the other half had burned.

“The Indians and berry pickers suffered terribly. Hundreds of Indians who were camping and picking berries in the woods were robbed of their all by the fire, their blankets burned, their stock killed and their tents and camp equipment destroyed. So it was with many white campers. No one will ever know just how many burned to death, for there may have been hundreds of berry pickers in the dense woods through which the fire ate.

“People who are still at Maulding’s place, Welch’s and at Rhododendron asked me to let the newspapers know that the danger was past, so that their friends and relatives may know they are safe. The stages are having trouble getting in and out and it will be several days before all those who desire to leave can get out.

“At Maulding’s hotel there are a Mr. McKnight of Portland, and his three sisters; Mrs. Rasmussen and two daughters; T.G. Green, and two children, Dr. Stolte’s wife and son of Douglas Taylor, formerly city engineer of Portland, are at the hotel. Mr. Taylor is out in the woods on a surveying trip. He did not encounter the flames.”

Reflections on the Mt Hood Forest Fires of 1910

This is one of the most detailed accounts I’ve found about the 1910 fires near our local communities from Brightwood to Rhododendron. It touches on places I know well and brings to life a time when fire danger meant loading what you could into a wagon and hoping the wind shifted.

Today we think of wildfire as a modern problem, but this reminds us it’s been with us a long time. I’ll continue sharing these kinds of historical pieces here as I dig deeper into the story of Mount Hood’s past — and if you’ve got local stories or family history connected to this era, I’d love to hear them.

Read here for another close call with a Mt Hood Forest Fire in 1952