A Mountain Legacy Remembered

A Cultural Bloom in the Heart of the Forest

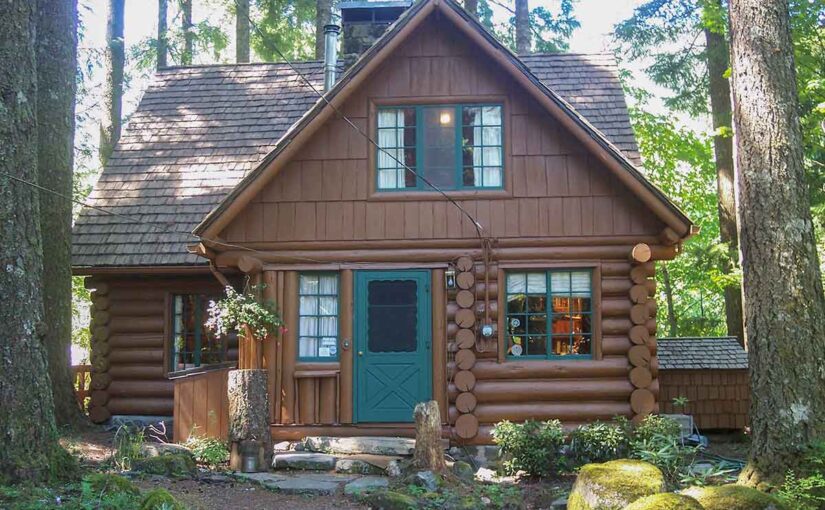

Just east of Portland, along the winding curves of Highway 26, sits Rhododendron, Oregon—a place not quite a town, but more than a roadside stop. Nestled in the folds of the Mount Hood National Forest, it’s a patchwork of tall trees, weathered cabins, and the kind of tight-knit community where everyone knows your dog’s name. In this scenic and soulful village, the Rhododendron Summer Theater took root. Though short-lived, the theater transformed Rhododendron into a vibrant cultural destination during the summer months.

A Village with Roots and Rhythm

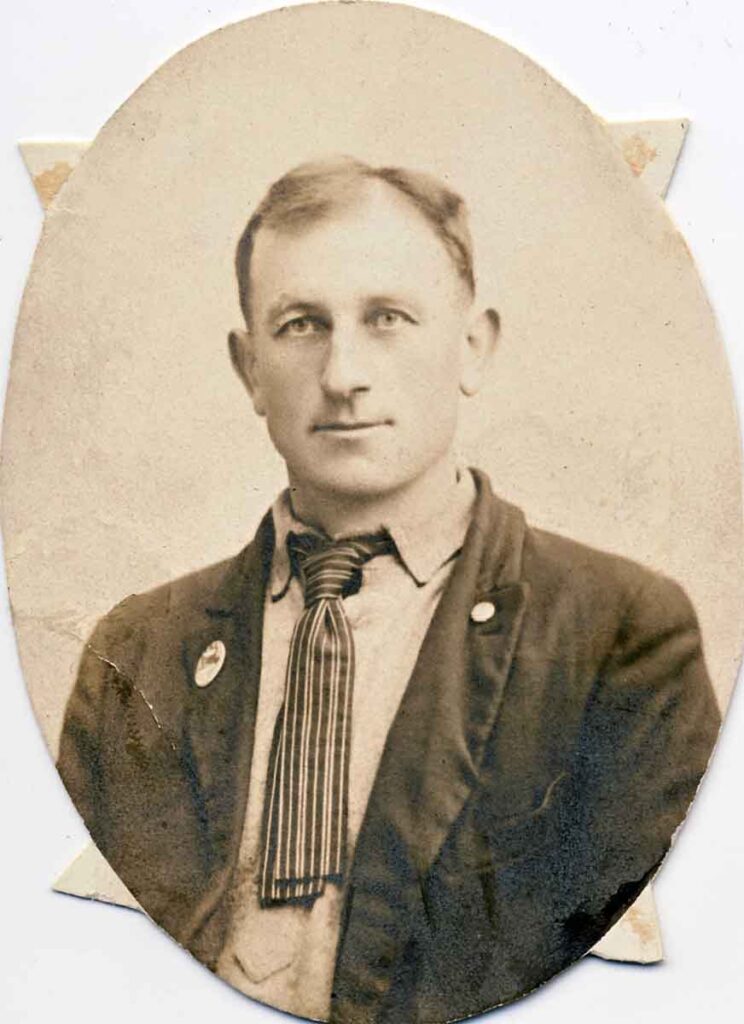

For decades, Rhododendron served as a peaceful retreat from city life. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, the town had settled into a familiar seasonal rhythm: snow in the winter, hikers and vacationers in the summer. However, one thing was still missing—live theater. That changed when Mark Allen arrived with a bold idea.

Allen—producer, director, and actor—had years of experience in summer stock productions. While others only saw a ski shop, he envisioned a stage. More specifically, he saw potential in Joie Smit’s ski shop, a modest structure near the Log Lodge. Behind it stood a second unused building. Allen imagined it filled with laughter and light beneath a roof that could open to the stars.

The Theater with a Sky for a Ceiling

With help from locals and fellow performers, Allen transformed that back building into the Rhododendron Summer Theater. The venue was small, a bit unconventional, and absolutely alive with character. Most unforgettable was the convertible roof—a hand-cranked panel that allowed plays to unfold under the open sky or close quickly when mountain weather rolled in.

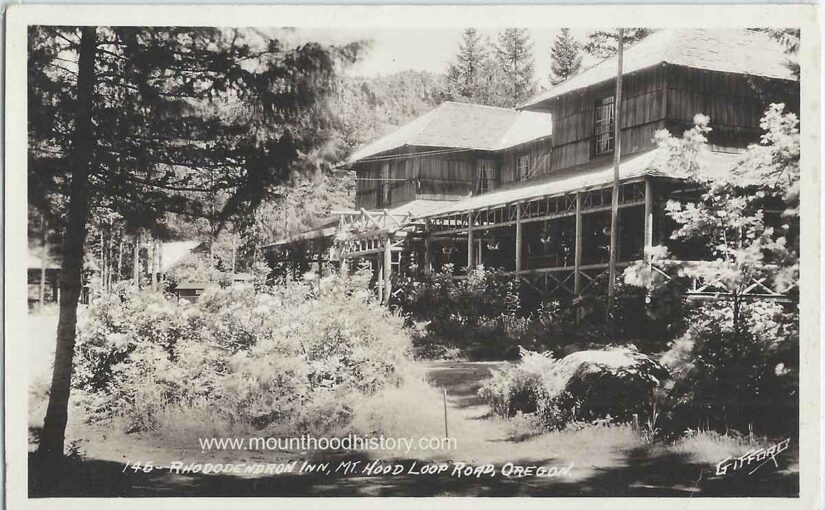

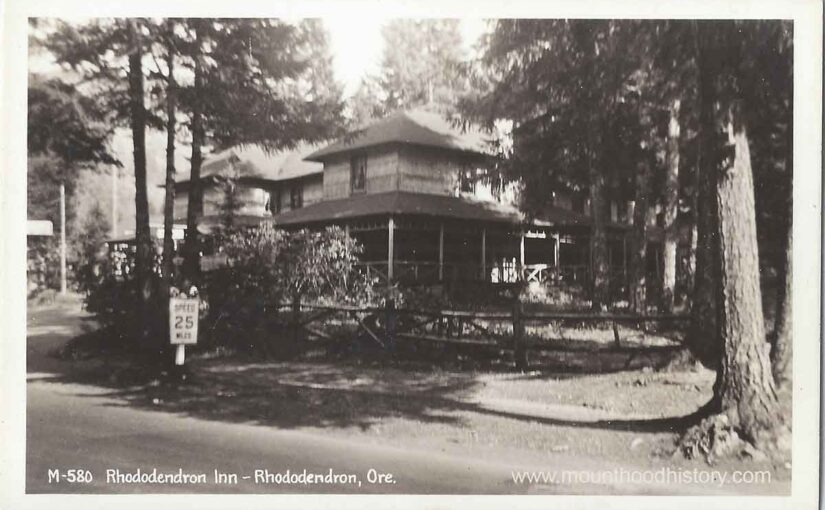

Right from the start, the community embraced the project. Residents from neighboring towns, Portland weekenders, and locals all played a part—whether as patrons, volunteers, or cast members. Among its most loyal supporters were Bill and Nancy Spencer, who owned the nearby Log Lodge. Not only did they encourage the project, but they also hosted actors and helped organize post-show gatherings. Their involvement gave the theater roots and a sense of place.

Thanks to their connections, the theater quickly earned its place in town life. It wasn’t just a novelty. Instead, it became a defining part of Rhododendron’s identity. Travelers might see a sign advertising the evening’s performance, then stop by the lodge for pie and updates on the cast.

Opening Night, 1961

The curtain rose on The Reluctant Debutante, a romantic comedy led by a cast of seven. The debut was a clear success. According to The Sunday Oregonian (July 2, 1961), a “capacity-plus” crowd filled the theater. All 165 reserved seats were taken, and at least 15 more guests grabbed folding chairs at the back.

It was a cool, cloudless night. The crew opened the roof so the audience could enjoy the show beneath the stars. That moment marked the beginning of the Rhododendron Summer Theater’s first full season.

The entire endeavor was built by the community. The Rhododendron Boosters Club organized funding through private donations and business sponsors. Even more notably, all labor was volunteered. After The Reluctant Debutante, the group followed up with a five-week run of The Moon Is Blue.

Curtain Call and Community

Each summer brought new shows and fresh energy. The company staged Neil Simon comedies, classics like Barefoot in the Park and The Seven Year Itch, and heartfelt dramas like Tunnel of Love. Auditions were held in Portland. Once selected, the actors lived in Rhododendron, quickly becoming familiar faces in the store, café, and along the trailheads.

Audiences sat close—shoulder to shoulder—often wrapped in blankets. Evenings buzzed with energy. Locals brought visiting family. Hikers stumbled into something delightful and stayed for the whole performance. For those few hours, Rhododendron became a mountaintop village of the arts.

From Rhododendron to Welches: The Final Act

By 1967, after six strong seasons, Mark Allen announced a change. The production company would relocate to Bowman’s Golf and Country Club in Welches, opening a new chapter as the Mount Hood Summer Theater. The new pavilion-style venue promised better amenities and long-term sustainability.

The seventh season opened on June 30, carrying forward the same spirit. However, it proved to be the final curtain. No further performances are recorded after that summer. Perhaps the mountain’s remoteness presented too many challenges. Then again, maybe the theater had simply fulfilled its purpose—bringing light, laughter, and community to the trees while it could.

A Legacy That Lingers

The theater building is gone now. The convertible roof no longer opens to the stars. Nevertheless, the memories remain vivid for those who were there.

They remember Joie Smith’s ski shop serving as the backstage entrance. They remember the warmth of the Spencers, and the buzz of opening nights. Most of all, they remember sitting in the woods, surrounded by friends and pine needles, as actors poured their hearts into each line.

The Rhododendron Summer Theater didn’t last forever—but it didn’t need to. Its brilliance endures in memory, woven into the story of the mountain.