Marmot Oregon is located along the last stretch of the Oregon Trail, the old plank covered Barlow Road. Between 1883 and 1930 it was a destination for many people that came to experience the great outdoors and to launch their adventures on Mount Hood.

Category: Mt Hood Loop Highway

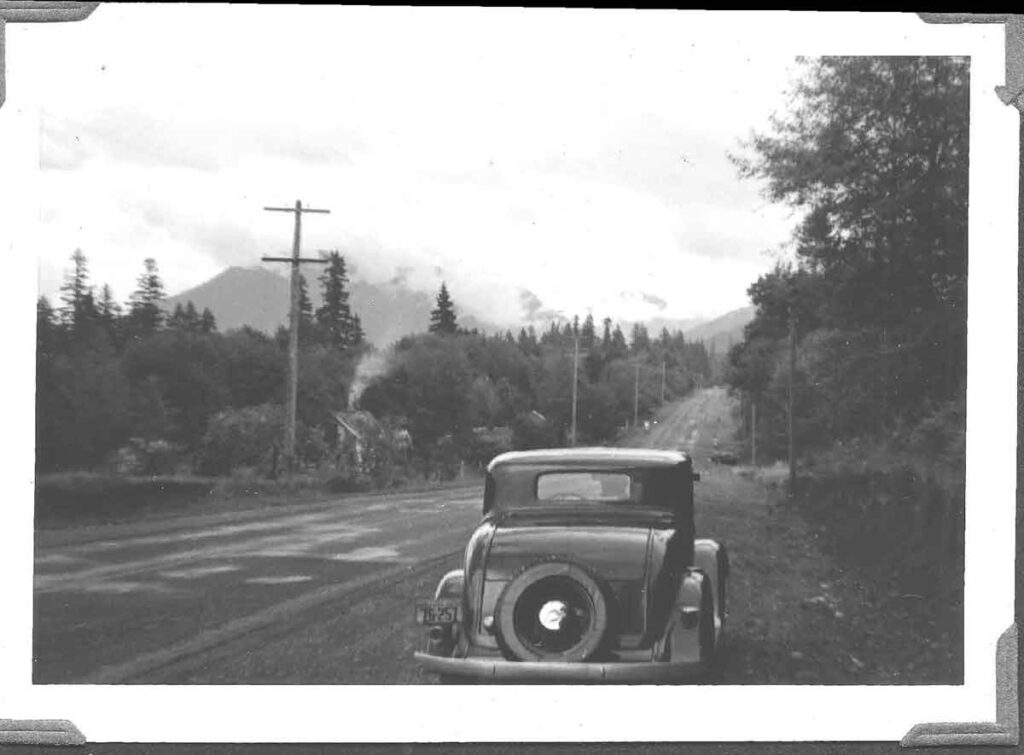

Mount Hood Highway at Alder Creek 1939

Alder Creek is a little town half way between Sandy and Welches Oregon on today’s Highway 26.

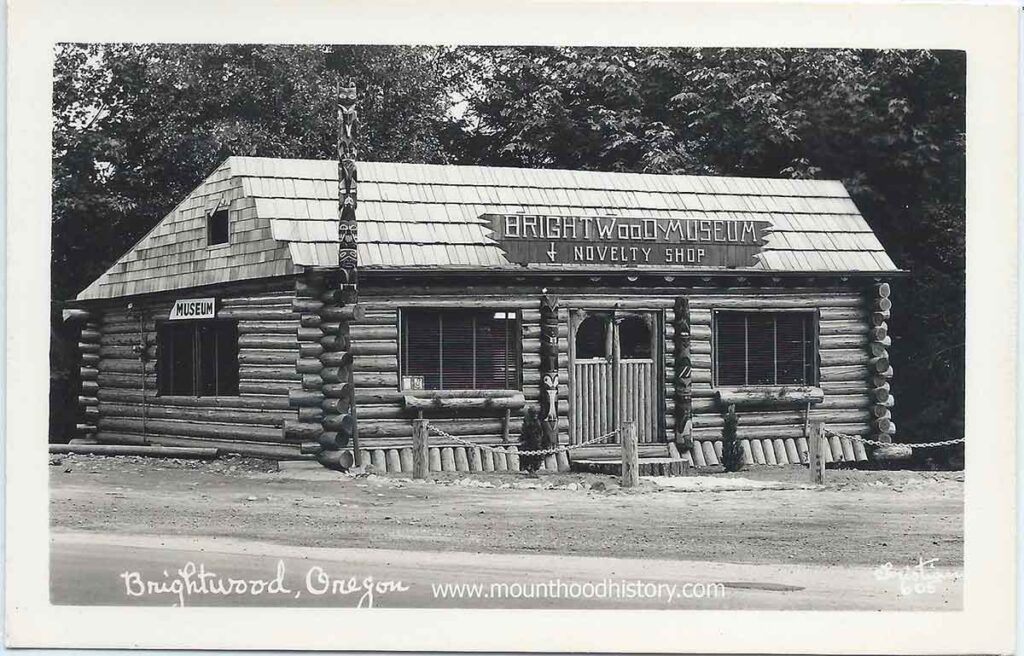

Brightwood Museum and Novelty Shop: Mt Hood Loop History

The Brightwood Museum and Novelty Shop. Many locals who remember this place in its heyday still call this the Snake Pit. In its lifetime it was several things, including a home.

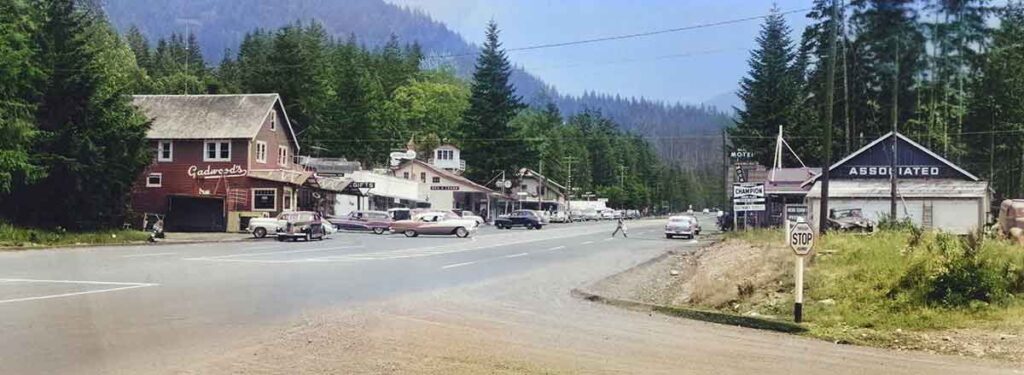

Rhododendron Oregon Centennial and History

a video to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the little Mount Hood village of Rhododendron Oregon.

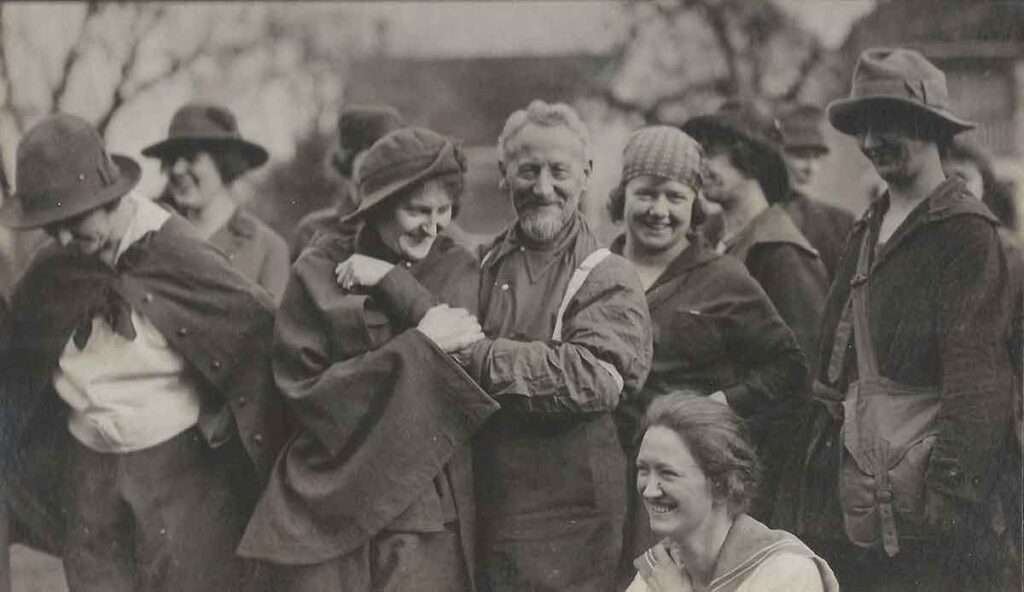

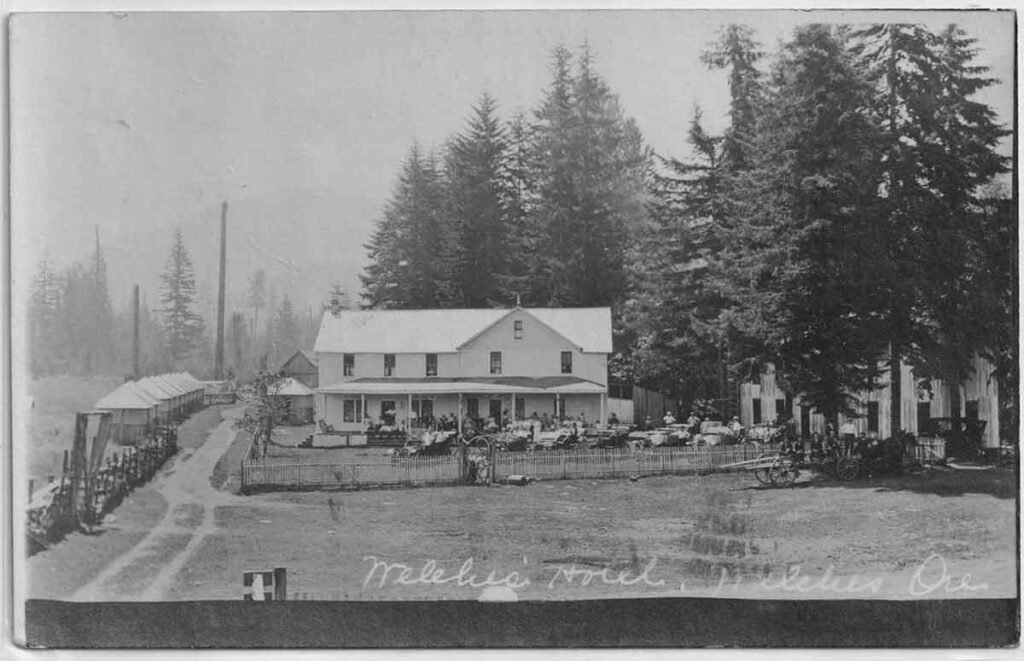

Uncle Sam Welch’s Ranch in Welches Oregon

Back before Welches became a destination it was a ranch, Samuel Welch and his son Billy homesteaded adjoining 160 acre sections of the Salmon River Valley on the southern side of Mount Hood.