Susette Franzetti Rhododendron Oregon – Pioneer of Hospitality

From the Swiss Alps to Oregon’s Mount Hood

Before Rhododendron, Oregon, became a known mountain getaway, Susette Franzetti helped build its identity. A Swiss hotelier with European training, she transformed the area with hospitality, real estate, and resilience. Ultimately, the story of Susette Franzetti Rhododendron Oregon is one of independence and quiet determination.

A Lifelong Passion for Hospitality

Susette Franzetti was born in 1879 near Lake Constance, Switzerland. After graduating high school, she studied French in Geneva and began training in hotels across Lugano, London, the Italian Riviera, and Corsica. She spoke seven languages and worked in the front office, purchasing, and guest services.

“You can’t be a successful resort keeper unless you really have in your heart the spirit of hospitality,” she once said.

Starting a New Life in America

In 1905, Susette immigrated to the United States. She married Emil Franzetti, a renowned European chef, and together they lived in New York, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. By 1909, they had settled in Portland, Oregon, where Emil became the head chef at The Quelle.

They were a powerhouse pair—Emil in the kitchen, Susette handling the business side.

Managing the Rhododendron Inn Alone

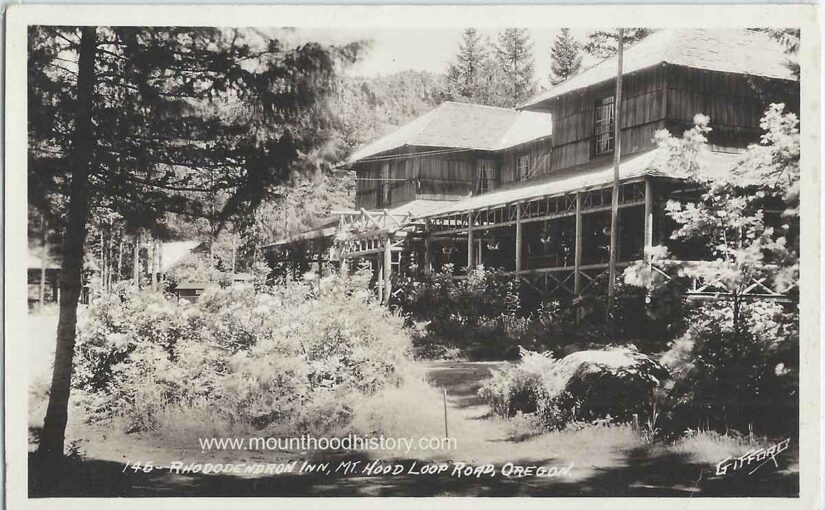

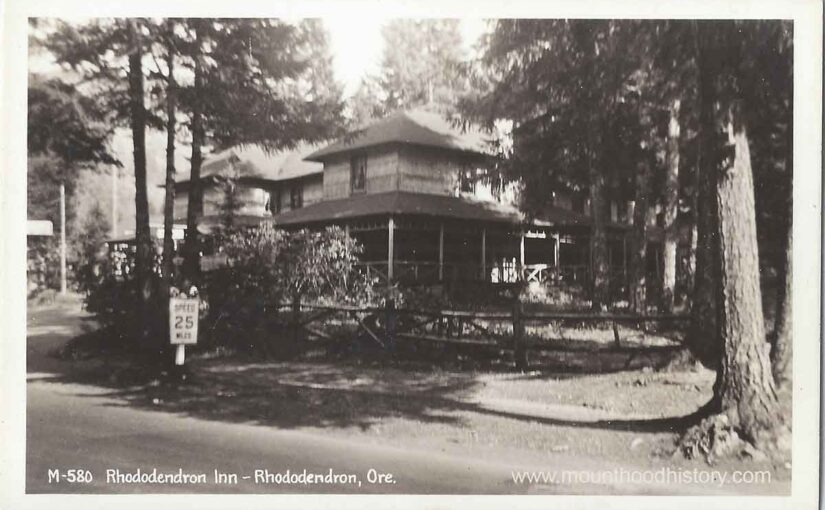

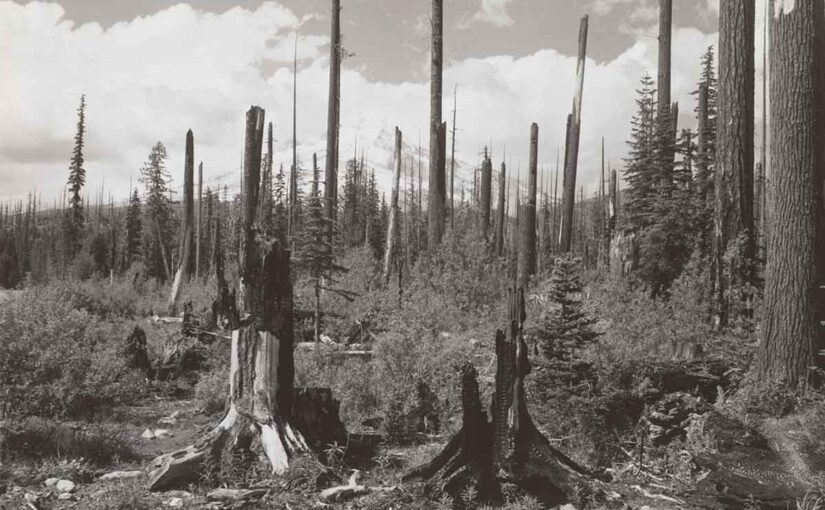

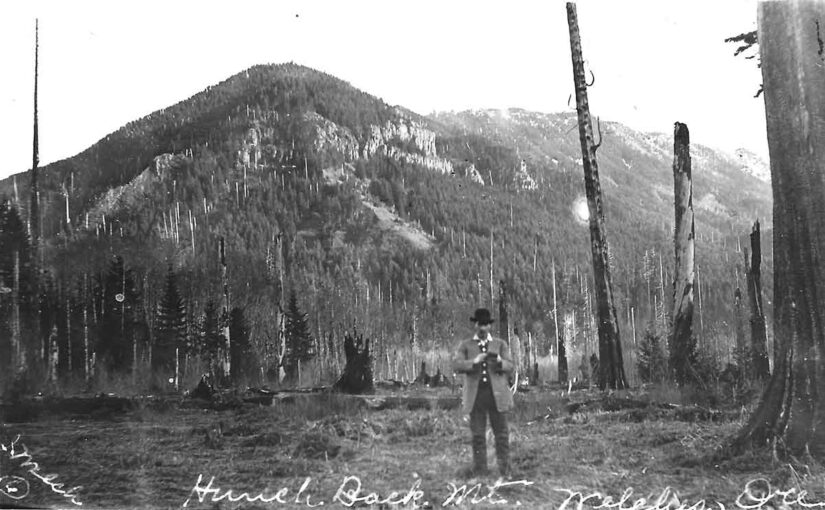

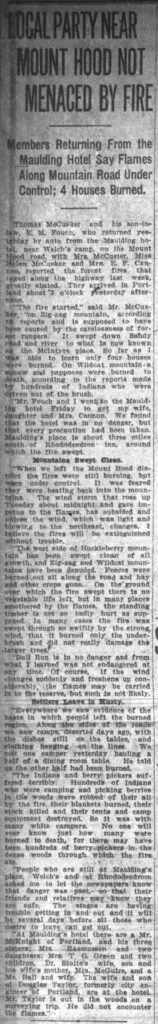

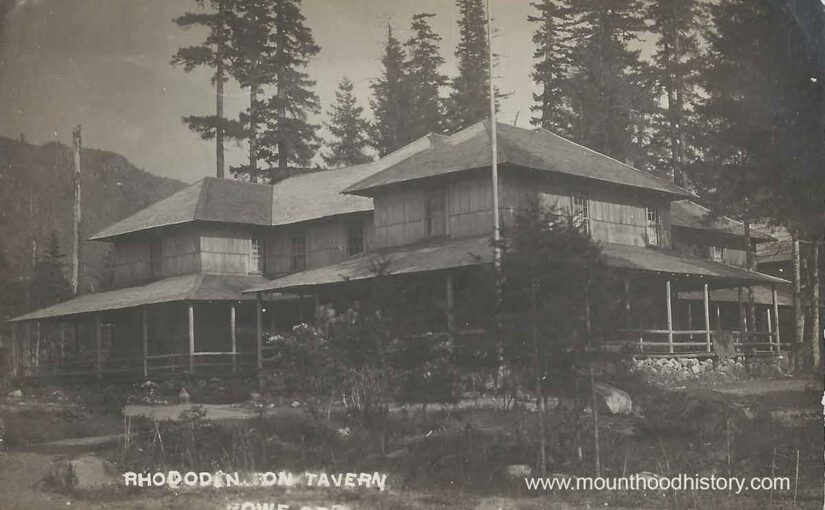

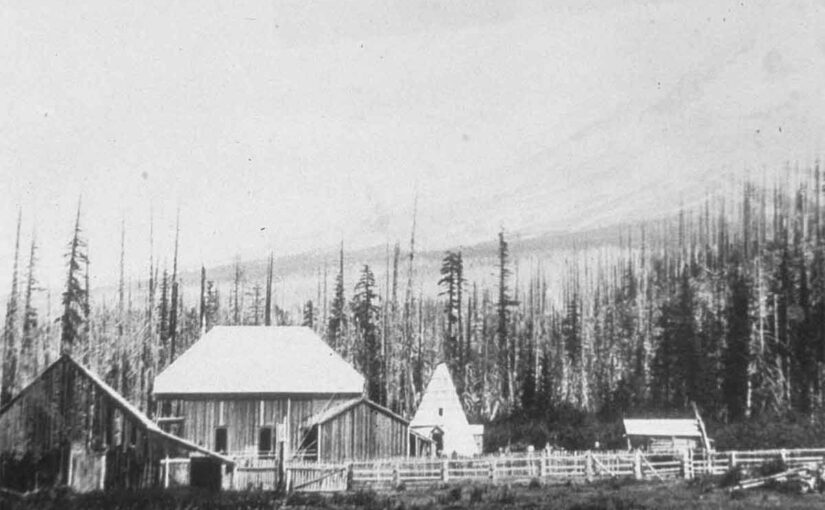

In 1911, the Franzettis purchased the Rhododendron Inn, originally developed by Portland’s former mayor, Henry S. Rowe. The 160-acre property quickly became a favorite stop for travelers and skiers.

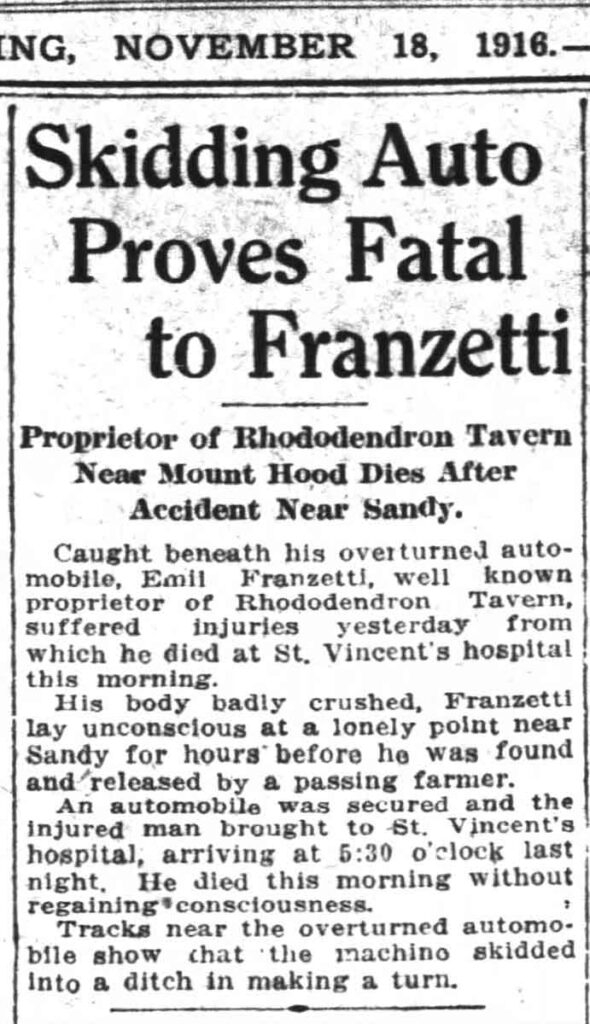

Tragedy struck in 1916 when Emil died in an automobile accident. Even so, Susette carried on. She ran the inn alone for seven years, continuing to serve guests and manage operations.

The Woman Who Helped Build Rhododendron

In 1923, Susette sold the Rhododendron Inn, but she didn’t slow down. She subdivided her land, built and sold 36 cottages, and helped shape what would become the town of Rhododendron. As a result, her sharp business sense and reputation for fairness left a lasting mark on the area.

In 1933, she said:

“I had 150 acres here, which I subdivided and sold in tracts and lots. I have built and sold 36 cottages here. Two-thirds of my property is already sold.”

Suitcases and Zeppelins: A Life of Travel

Despite living in the forest, Susette never stopped exploring. In 1925, she traveled to Europe via the Panama Canal. Four years later, she began a 16-month world tour, which included a Graf Zeppelin flight over England. Then in 1937, she boarded a ship in Portland bound for Naples to reunite with her brother from Switzerland.

Her love for travel and learning never faded.

Final Years and an Unseen Legacy

Susette spent her final years at Willamette Manor Convalescent Center, where she lived from 1957 until her death in 1972 at the age of 93. Her ashes were returned to her hometown of Romanshorn, Switzerland.

Although she left no surviving family, her influence still echoes through the cabins and lots she developed. To this day, her story is inseparable from the history of Rhododendron, Oregon.

Susette Franzetti’s Enduring Spirit

Few people did more to shape the look and spirit of early Rhododendron than Susette Franzetti. With her world-class hospitality background and independent spirit, she built a life rooted in generosity, vision, and perseverance.

The next time you walk the trails or pass through Rhododendron, picture a woman who once ran the inn, subdivided the land, and brought global perspective to a quiet corner of Oregon’s mountains.