I’ve spent a lot of time talking with old-timers and the family members of folks who’ve lived up here in the Mountain Community for years. In one or two conversations, I’d heard tell of a woman who gained local notoriety for killing a bear that invaded her space with a garden hoe.

Tag: zigzag oregon

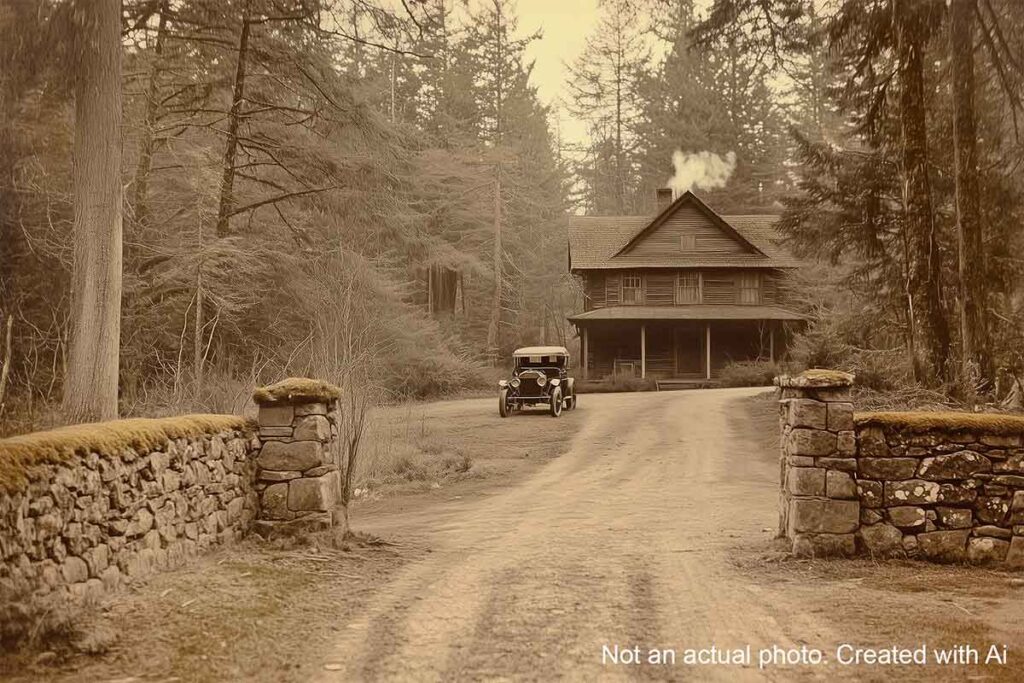

Howard’s Hotel at Sharon Springs

Howard’s Hotel at Sharon Springs: A Lost Piece of Zigzag’s History

Zigzag Cabin Owner: A Local Legend

Montavilla neighborhood of Dr. William DeVeny. Known as the “Buffalo Bill of Portland,” DeVeny left a lasting legacy in Montavilla and the Mount Hood region.