A Loss on The Mountain: The Deaths of Henry and Fred Steiner

Tragedy Beneath the Tall Trees

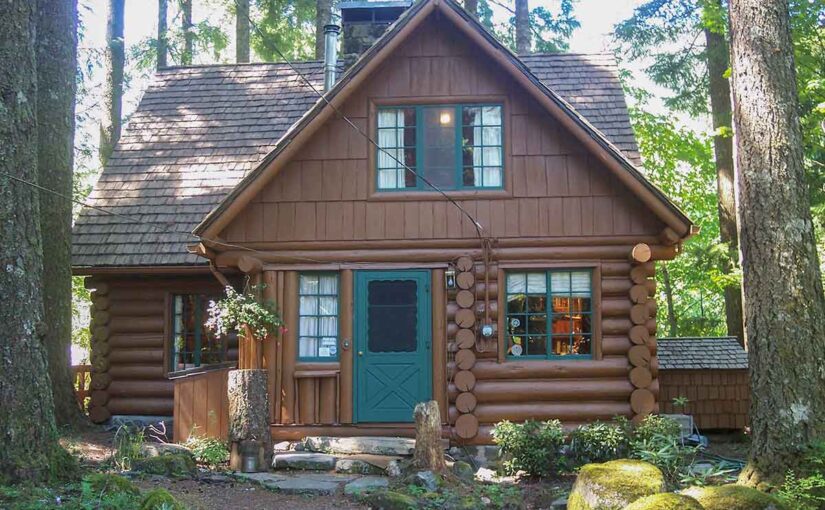

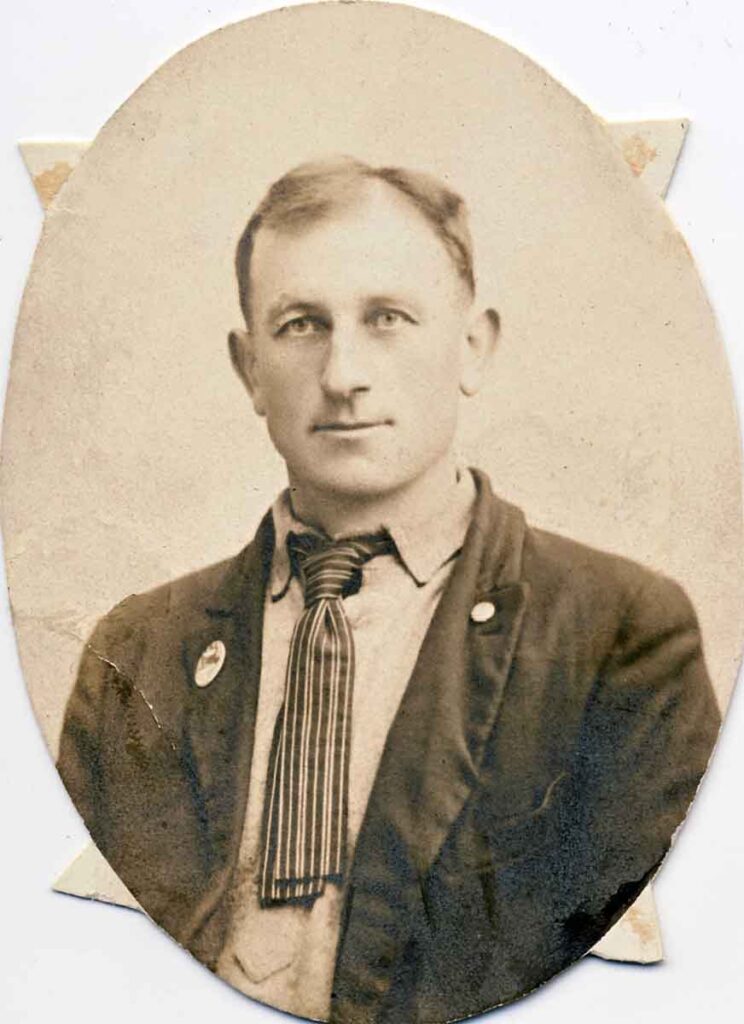

Henry Steiner was known throughout the Mount Hood region as a master builder of log homes. He and his wife, Mollie, raised their family in Brightwood, where Henry built dozens of rustic cabins that still stand today. His sons, including Fred, learned the trade from him and often worked alongside him. The Henry and Fred Steiner deaths in 1953 would mark one of the darkest moments in the community’s history, but by then, the “Steiner cabin” had already become a local hallmark of hand-built timber construction—steep-roofed, river-stone anchored, and shaped by hand rather than machine.

In the spring of 1953, the Henry and Fred Steiner deaths cast a long shadow over the Mount Hood community. Henry, a master cabin builder, vanished into the forest near Brightwood. Days later, his son Fred—who had traveled north from California to help find him—drowned in the river during the search. Their story is one of family, legacy, and quiet tragedy in the same forests where the cabins they built still stand.

The Disappearance of Henry Steiner

On Tuesday, April 7, 75-year-old Henry Steiner vanished from the wooded land near his home in Brightwood, Oregon. Though elderly, he remained active and independent. At first it was thought that he left to simply walk the forest trails he knew so well. When he failed to return, concern grew quickly.

State police, Clackamas County deputies, U.S. Forest Service crews, and Brightwood locals mounted a widespread search across the steep, forested terrain near Mount Hood. By Thursday, they had ruled out the possibility that he had taken a bus to visit family. All signs pointed to something having gone wrong in the woods.

Fred Steiner’s Search and Sacrifice

Fred Arthur Steiner, age 39, was working as a logger in Eureka, California when he learned of his father’s disappearance. He returned home to Brightwood to help with the search.

On Saturday, April 11, Fred set out with his brothers to search along the Sandy and Salmon Rivers. He entered the fast-moving water in a rubber life raft, with a rope attached to shore for safety. As he reached the confluence near Salmon River, the raft overturned in the rough current.

Fred could not swim, and despite the rope, he was swept downstream nearly a mile. Witnesses, including his brother John Steiner and brother-in-law Pat Carey, could do nothing. Cliff Finnell of Brightwood recovered Fred from the water after roughly 20 minutes. The Sandy Fire Department tried to revive him using an inhalator. He was rushed to Providence Hospital in Portland, where he was pronounced dead on arrival.

Discovery of Henry Steiner’s Body

Three weeks later, on Sunday, April 26, Henry Steiner’s body was discovered along Hackett Creek, about 1½ miles northeast of Brightwood. Two people—Otto Laur of Brightwood and Lynn Fuller of Portland—were inspecting Fuller’s summer cabin when they came across the scene.

Henry had apparently sat down to rest on a stump, perhaps fatigued or disoriented, and fallen backward. His cane was still propped against the stump when his body was found. The Clackamas County Coroner, Ray Rilance, reported no sign of foul play. The cause of death was assumed to be a heart attack. His body was taken to the Holman, Hankins & Rilance Funeral Home in Oregon City.

Remembering the Henry and Fred Steiner Deaths

Henry Steiner was more than a builder—he was an artist in wood and stone. His cabins, known today as Steiner Cabins, grace the slopes of Mount Hood with steep-pitched roofs, peeled-logs, arched doorways, Sunray decoration above the front door, and basalt fireplaces pulled from local creeks or built by local stonemason George Pinner. He blended Old World technique with Northwest sensibility.

Fred, a logger by trade, shared his father’s connection to the forest and deep sense of family. He died doing what many hope they would have the strength to do—trying to bring a loved one home.

The Henry and Fred Steiner deaths marked one of the most tragic chapters in the history of the Mount Hood corridor. But the cabins still stand, warmed by fires in hearths they built, nestled in groves they once walked. And in those woods, their legacy quietly remains.